by Earl R. Aguilera

First published January 2022

Download full article PDF here.

Abstract

Over the course of the past two decades, a growing number of scholars have mapped the ways that ideologies of whiteness have pervaded videogames and other kinds of digital interactive media. Oftentimes, the most discussed examples of whiteness-in-gaming involve the features of videogames that are the most readily apparent to outside observers. These include a game’s multimodal representations of the racialized (or oftentimes, de-racialized) features of characters, groups, and societies in virtual worlds. On the other hand, scholarship that has focused on the fundamentally procedural nature of games—that is, the fact that games are fundamentally composed of and defined by rules and rule systems—points to a less visible dimension of the pervasive nature of whiteness in gaming. Taking the concept of procedurality as a theoretical starting point, this essay offers a framing of whiteness-in-gaming as a proceduralized ideology: a way of knowing/doing/being in the world that is embedded in and circulated through computational technologies like videogames. I illustrate this framing through examples of proceduralized whiteness in the character creation tropes of fantasy roleplaying games, the overarching goal structures of games of empire, and the design of player-world interactions that have come to dominate narratively-driven games. I contrast these by highlighting sites of resistance to proceduralized whiteness that are exemplified in the designs of Indigenous-centered games such as Never Alone: Kisima Ingitchuna (2014), When the Rivers Were Trails (2019), and Terra Nova (2019).

Amidst calls for increased representation in games, the popular online multiplayer game Apex Legends (2019) was highlighted for featuring characters of a wide range of genders, skin tones, hair textures, spoken accents, and physical abilities (Lin, 2021). Amidst calls to address racialized police brutality around the world, the livestream team Black Girl Gamers exploded in popularity online (Johnson, 2021). And amidst a renaissance of tabletop roleplaying games across player demographics, Dungeons & Dragons publisher Wizards of the Coast has released statements addressing topics of racism, ethnocentrism, and white supremacy that have historically underpinned much of fantasy gaming (Marshall, 2020).

These and other seemingly progressive developments should absolutely be acknowledged alongside movements to diversify popular media more broadly. At the same time, they can also obscure other aspects of gaming that continue to uphold, reinforce, and circulate the mythical norm of whiteness (Lorde, 2012). The purpose of this essay is to examine whiteness-in-gaming from a proceduralist perspective—that is, one that examines games as fundamentally composed of rules and rule systems (Bogost, 2010; Murray, 2017; Zimmerman & Salen, 2003). Far from being ideologically neutral, these systems are mutually constituted by the beliefs, perspectives, and worldviews of their creators, who in turn are not immune to dominant social/cultural norms, beliefs, and biases (Benjamin, 2019; Eubanks, 2018; Noble, 2018). Thus, this essay offers a theoretical framing of whiteness-in-gaming as a proceduralized ideology—that is, a way of knowing/doing/being in the world that is embedded in and circulated through computational technologies like videogames.

While the concept of whiteness in contemporary society has a complex and shifting definition, I begin the essay by unpacking the key features of whiteness that are central to this argument—namely, the ways in which whiteness has manifested in narrative tropes that have come to dominate the fantasy worlds in which videogames are often set. I then describe the role of procedurality in videogames, and in particular, the ways that procedural tropes (often referred to as a game’s “mechanics”) can also serve as expressions of meaning beyond a game’s visual, audio, and narrative content. Bringing these ideas together, I turn to an examination of whiteness as a proceduralized ideology that can be circulated through videogames and other interactive media. Finally, I close the essay with an overview of pathways for resisting this proceduralized whiteness through reconfigured relations at the sites of production, reception, and within the games themselves.

I approach this work from the perspective of a lifelong gamer, a person of color, and a scholar of digital interactive media, whose experiences with games are often framed by the intersection of these identities. While I draw largely from Indigenous perspectives to theorize what it means to reconfigure relations in gaming, I continue to reflect on how this contrasts with my own positionality as the son of immigrant parents living in occupied Indigenous lands under a settler-colonial state. Rather than seeking to provide a singular, prescriptive “solution” to the challenges that whiteness-in-gaming presents, I hope this piece instead serves to encourage reflection, dialogue, and most importantly, a reimagining of the vast potential of gaming as a medium for telling stories and crafting experiences that go beyond dominant ideologies.

The Mythological Construction of Whiteness

In “Age, Race, Class and Sex: Women Redefining Difference,” Lorde writes:

Somewhere, on the edge of consciousness, there is what I call a mythical norm, which each one of us within our hearts knows “that is not me.” In America, this norm is usually defined as white, thin, male, young, heterosexual, Christian, and financially secure. It is with this mythical norm that the trappings of power reside within this society. (2012, p. 106)

In her conceptualization of whiteness as a “mythical norm,” Lorde encapsulates what has become a consensus principle of the sociology of race: whiteness, like all other racial categorizations, is much more a product of social construction than it is of biological distinction. Further, as is characteristic of other mythologies, the idea of whiteness has been constructed, codified, and modified over time, often times through intentional and often insidious means, including the so-called “one drop rule” implemented by European colonizers in an attempt to circumscribe both indigeneity and Blackness as racialized identities (Tallbear, 2003). Within the world of popular media, scholars such as Leonard (2007) have highlighted the ways ideologies of racialization run deep within videogames and their representations of professional sports and other social institutions. In the following sections, I unpack three key features of whiteness that have manifested in narrative tropes that have come to dominate the many worlds that gamers inhabit.

Whiteness as (De)Racialization

Though skin color is often cited as one basis from which whiteness constructs its logics, history demonstrates that whiteness has been utilized as both a tool for racializing those deemed non-white, as well as a tool for deracializing people who take themselves as the normative reference for conversations about race (Henry & Tator, 2006). On the one hand, the imperial powers of Europe often justified their colonizing, invasion, settlement, and occupation of Indigenous lands by mythologizing racial features of the people they invaded: from skin tone and facial structure to hair texture, proclivity to hard labor, etc. (Collins, 2002). This has given rise to numerous dehumanizing ideologies, from the “noble savage” of English literature to the “limpeza de sangre,” (purity of blood, a system of discrimination in Spain and Portugal conflating aspects of physical appearance, culture, and biology). Perhaps the most widely discussed examples of this were the wide range of ideological justifications for the enslavement of African peoples in the Americas, and the legacies of anti-Black legal structures, cultural beliefs, and social hierarchies that persist in the U.S. and Canada. At the same time, whiteness has also been deployed as an ideological tool for de-racializing people who believe they are white via the occupation of a normative category. In the words of Henry and Tator: “[W]hiteness is considered to be the universal … and allows one to think and speak as if whiteness described and defined the world” (p. 327). This in turn gives rise to the possibility of race-blind ideologies, as well as the privileged claim that one “does not see color” (Bonilla-Silva, 2006).

Whiteness as a Colonizing Logic

A second feature of whiteness is the way that it has been historically rooted in and deployed as an extension of imperialism and colonialism. As Collins (2002), Ahmed (2012), Dunbar-Ortiz (2014), and others have established: a fundamental justification for the imperial invasion, colonization, and continued occupations by European and U.S. powers has been a belief in a kind of racial superiority of people of European descent over Black, Indigenous, and Asiatic peoples around the world. This conception of superiority, however, requires a reference point to begin its logics. Superiority is this useful tool in the ideology of whiteness. As Kivel (2011) frames it, “Racism is based on the concept of whiteness—a powerful fiction enforced by power and violence. Whiteness is a constantly shifting boundary separating those who are entitled to have certain privileges from those whose exploitation and vulnerability to violence is justified by their not being white” ( p.19). These fictions have often been framed by their originators as benevolent in nature—for example, the “civilizing” missions of Catholic missionaries in Canada and the U.S. President William Taft’s framing of the peoples of the occupied Philippine islands as “our little brown brothers.” Regardless of their rhetorical positioning, however, the histories of genocide, enslavement, and cultural erasure that result from the marriage of whiteness and imperialism suggest a very different reality.

Whiteness as a Relational Positioning

A third feature of ideological whiteness is that it can be understood as relational in at least two senses. In one sense, whiteness is relational because it can only exist in relation or opposition to an “other” racialized category (non-white) in a hierarchy that is produced by ideologies of whiteness. It is only in defining “others” that whiteness can define itself (Levine-Rasky, 2012). In another sense, however, whiteness is relational because it represents a certain way of conceiving one’s relationships with other people and with the natural world. As Frankenburg (1993) argues, whiteness shapes how certain people view themselves and others, and places the people who believe they are white in a place of structural advantage where white cultural norms and practices go unnamed and unquestioned. Historically, it positions animals, plants, and land as “natural resources” to be extracted, utilized, and dominated rather than beings with equal relational status and sovereign claims to autonomy, growth, and existence.

These three aspects of ideological whiteness—a tool for racialization, a justification and extension of imperial/colonial logics, and a relational category—provide a brief overview of the complex nature of whiteness as it operates in society. It is beyond the scope of this essay to provide a comprehensive overview of whiteness; however, it is my hope that an analysis of these three aspects, as they pertain to contemporary videogames, invites further exploration.

Proceduralized Ideologies Within and Beyond Videogames

Before turning to the ways in which ideologies of whiteness are embedded in and circulated through the procedural design of videogames, I want to briefly outline the idea of proceduralized ideologies and what they have to do with gaming.

Whether designed to be played on city streets, kitchen tabletops, or computers, games are fundamentally defined by processes, which are in turn enacted through rules and rule systems (Zimmerman & Salen, 2003). This view does not suggest that the only meaningful analysis of games is as procedural artifacts—games can also be understood through the lens of play (Vidakis et al., 2014); story (Carlquist, 2013); culture (Zimmerman & Salen, 2003); and identity (Gee, 2007); among other perspectives. However, as Bogost (2010), Murray (2018), and Wardrip-Fruin (2020) have argued, looking at games as fundamentally procedural in nature can provide important insights into the communicative power of the medium that other perspectives may overlook.

Like all software, videogames play a role in actively constructing ideological visions of social worlds, enrolling users into these social worlds, and maintaining or transforming material relations and power asymmetries. An essential part of how videogames operate in the ideological realm is through the translation of these ideologies into rules and rule systems—a process I will refer to as proceduralization.

Given that most proceduralization in videogames happens via digital computing, we can understand proceduralization as operating in at least four ways:

- Repetition. Unlike a book, which is read by a single person once or a few times, popular games can reinforce ideological constructions through repeated use.

- Scale. Because of the popularity and increasing access to games, more and more people can experience the ideological dimensions of videogames now than ever before.

- Automaticity. Games rely on processes that are triggered automatically given certain human inputs, giving the feeling of “naturalness” when playing them.

- Invisibility. Computational processes underlying platforms are usually imperceptible to users. Rendering these processes invisible makes them difficult to understand let alone critique their influence.

The idea of procedure as a resource for expressing meaning has also been developed in Bogost’s (2010) concept of procedural rhetoric, which builds on the foundations of rhetoric as the art of making claims about the world. Procedural rhetoric extends logocentric and perceptual multimodal traditions of rhetoric by addressing the art of persuasion through processes, such as the rule systems that govern videogames, legal proceedings, or even economic transactions. While there are many things that can be proceduralized through computational means, I focus in this essay on the ways that ideological constructions, such whiteness, can be embedded in, and reinforced through the procedural design of games.

I define ideology in this essay as, “mental frameworks—the languages, the concepts, categories, imagery of thought, and the systems of representation—which different classes and social groups deploy in order to make sense of, define, figure out and render intelligible the way society works” (Hall, 1986, p. 29). Following Hall, I highlight the connection between ideology, power, and hegemony, that is, the ways particular ideologies come to dominate the thinking in a particular context that aid in the maintenance of power and material relations, here through notions of whiteness, race, humanity, and culture (Abercrombie & Turner, 1978).

Bringing these ideas together, I have used the term proceduralized ideologies to describe the particular ideological constructions that are embedded in and circulated through procedural means.

Given the ideas I have discussed so far in this article and in related theorization discussed elsewhere, I also suggest the following preliminary observations about proceduralized ideologies in videogames:

- Given the computational nature of videogames, understanding the properties of repetition, automaticity, invisibility, and scale can help us better frame proceduralized ideologies in relation to broader sociotechnical contexts. The potential for independent games like Never Alone (Upper One Games, 2014) depends, in part, on how popularized and widespread they become. In contrast, a game like America’s Army (United States Army, 2002), which was distributed by the U.S. military as a recruiting tool, is imbued with a very different potential for performing its ideological work.

- While videogames, like the media forms that came before them, are ideologically contested and value-laden artifacts, not all the ideological work in games is performed through procedural means. For example, the ideological construction of native and Indigenous peoples as bystanders to and instruments for American settler-colonizers in The Oregon Trail (MECC, 1974) was largely expressed through linguistic and visual modes (Longboat, 2019).

- Related to this point, proceduralized ideologies in videogames cannot solely be understood through a complete abstraction and separation of procedural resources into logical structures, mathematical operations, and computer code. Instead, these resources integrate with perceptual elements—graphics, sound, and language—to produce meaning potentials evident only in the full ensemble of multimodality (Hawreliak, 2018).

- Finally, in line with prior principles fundamental to social semiotics, an analysis of proceduralized ideologies in videogames should be informed by an understanding of the sites of production, reception, and dissemination which encompass the broader sociocultural context in which videogames exist (Rose, 2016).

Examples of proceduralized ideologies beyond gaming include the settler-colonial cities (but not Indigenous territories) that are recognized as “valid” locations in geotagging social media, the weighting of emoji-like “reactions” underpinning social media algorithms, and the linguistic accents that are coded as intelligible within speech-to-text software. When these proceduralized ideologies are not critically examined, we run the risk of allowing those experiences to frame more and more of our technologically mediated practices in ways that maintain—even exacerbate—existing inequalities. (Benjamin, 2019; de Roock, 2021).

Proceduralizing Whiteness: Three Examples

With “proceduralized ideologies” in mind we can turn to the question of how whiteness, as an ideological construction, manifests in the procedural design of videogames.

“Humanity” as Proximity to Whiteness

The first example I will highlight centers the character-creation systems that have become a defining feature of western roleplaying games (WRPGs). In contrast to the design of JRPGs (Japanese roleplaying games), which feature predefined protagonists with their own background, goals, and narrative trajectory, WRPGs have instead followed in the footsteps of tabletop roleplaying games (TTRPGs) like Dungeons and Dragons. In these systems, players are given a set of tools with which to generate a customized in-game character, which players then control throughout the game’s progression. It is in these procedural design character creation systems that we can glimpse both the racializing and de-racializing nature of proceduralized witness in gaming.

As Sturtevant (2017) points out in his essay “Race: The Original Sin of Fantasy Gaming,” one of the core aspects of character creation systems—whether in TTRPG or their digital WRPG successors is the conflation of race, culture, and ability, which Sturtevant traces back to the fantasy writing of J.R.R. Tolkien. Echoing historical traditions of Eurocentric views of whiteness as a reference point for racialized categories, popular game franchises like Baldur’s Gate (Larian Studios, 1998), World of Warcraft (Blizzard Entertainment, 2004), and Divinity: Original Sin (Larian Studios, 2014), feature the ability to choose non-human (but nevertheless intelligent) “races” that grant bonuses and penalties to a character’s ability scores, along with an illustration of cultural norms and other defining traits. Simply replacing the label of “race” with the concept of “species,” as in spacefaring games like Mass Effect (Microsoft Game Studios, 2007), may seem like a straightforward solution to this issue—that is, until we examine how human and non-human races are represented in these worlds.

Taking the massively popular Word of Warcraft (Blizzard Entertainment, 2004) as an example, we can see that the humans of the world are typically stylized according to medieval European tropes: knights in armor, castles of stone, and imperial monarchies. Contrast this with the portrayal of the Tauren, a non-human race of anthropomorphic bull-like creatures, which draws heavily from tropes that have been used to characterize the racialized Native and Indigenous peoples of the Americas—tepees, totems, and a spirituality centered on the natural world, etc. (Longboat, 2019).

Figure 1: A screenshot from the World of Warcraft (Blizzard Entertainment, 2004) character creation screen.

Similarly, the Pandaren, a panda-like species featured in an expansion to WoW, is characterized by tropes associated with broadly flattened stereotypes of “Asian” culture—from naming conventions to style of dress and architectural designs—defined in opposition to whiteness. It at this intersection of procedurality and worldbuilding that we see clear echoes of how “being human” is represented through proximity to whiteness, whereas to be nonhuman is represented through its distance from it. While the various anthropomorphic species of WoW—including the Orcs, the Tauren, the Night Elves, and the Pandaren represent analogues of various facets of human nature they are nevertheless de-humanized through a variety of procedural and perceptual modes (game mechanics, visual design, backstory etc.). On the other hand, species such as the Humans, Elves, and even Dwarves are marked by analogies to both Eurocentric history (knights in armor) or Eurocentric fantasy (light-skinned Dwarves all speaking in Scottish Brogue).

Contrast this design of proceduralized whiteness with how players are positioned to select a clan in the digital game When the Rivers Were Trails (LaPensée, 2019), where players explore an Anishinaabe perspective on Indigenous land displacement in the U.S. This design offers a set of meaningful choices that procedurally impact gameplay in different ways while avoiding the racialized procedural and representational pitfalls of the Western RPG genre.

Figure 2: Clan selection screen from When the Rivers Were Trails (LaPensée, 2019).

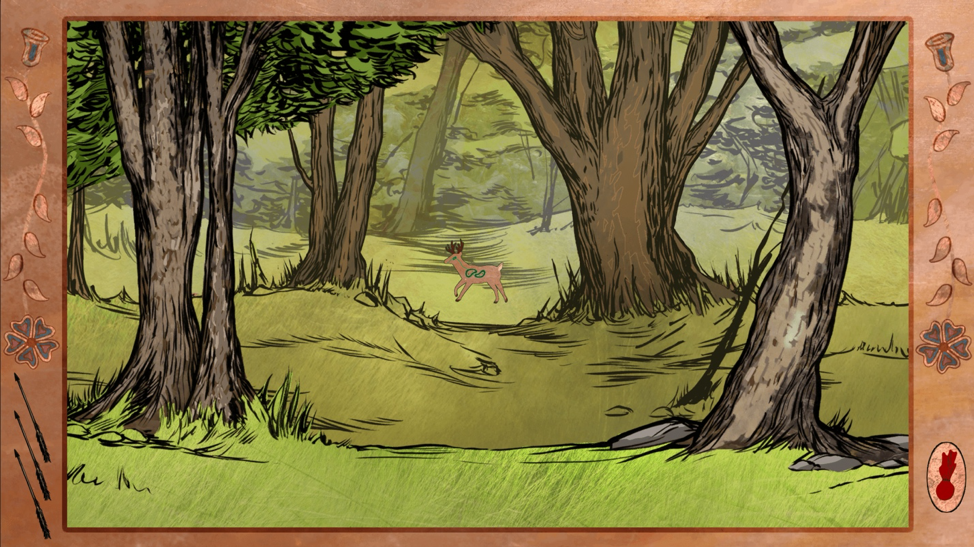

Beyond this element of procedural design, the significance of When the Rivers Were Trails (LaPensée, 2019) also lies in its direct subversion of procedural and perceptual multimodal tropes embodied in games like The Oregon Trail (MECC, 1974). On its face, When the Rivers Were Trails seems to follow many of the procedural conventions of The Oregon Trail, from geographic traversal across a portion of the U.S. map to the role-playing dialogue choices offered to players at various points of the journey, to hunting and fishing mini-games spread throughout the experience.

Figure 3: Hunting mini-game embedded into When the Rivers Were Trails

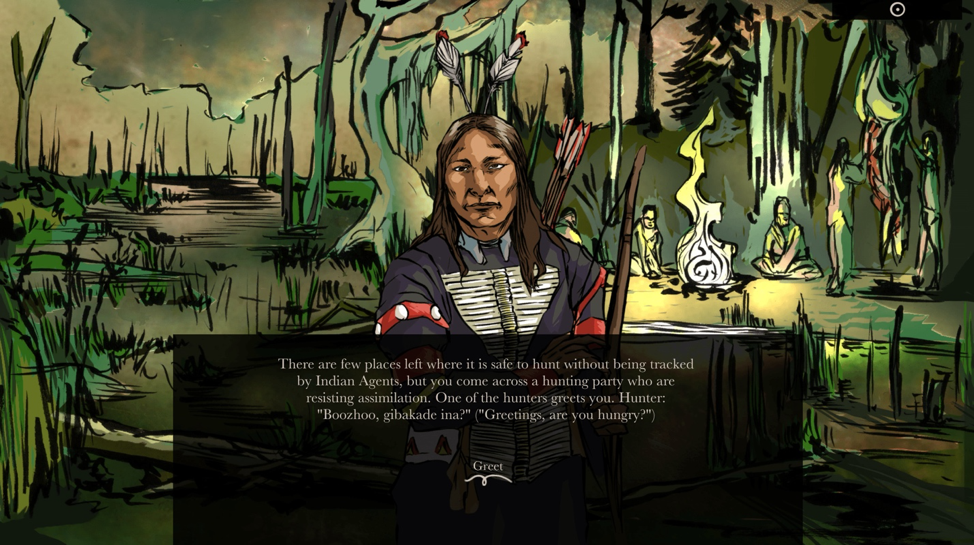

However, The Oregon Trail (MECC, 1974) notably positions Indigenous peoples as passive observers to / instruments of white settler colonization, which is the driving narrative of the game. In contrast, When the Rivers Were Trails (LaPensée, 2019) puts players in the shoes of an Anishinaabeg in the 1890s who has been displaced from their traditional territory in Minnesota and heads west to California, encountering Indian Agents, meeting people from different nations, and otherwise acting agentically and intentionally to balance their wellbeing and relations with those they meet along the trail. As I have noted in the theoretical framing guiding this analysis, the procedural design of When the Rivers Were Trails takes on different meaning potentials altogether when enmeshed with the artistic style, narrative dialogue, and sound design of the game, which featured contributions from over thirty Indigenous creators.

Figure 4: Character dialogue screen from When the Rivers Were Trails

Other westernized games, such as Obsidian Entertainment’s Pillars of Eternity (2015), have made attempts to revise the historical character creation systems of the WRPG genre. For example, the “default” human selection in the game no longer generates a character of overtly European descent, and the game adds “culture” as an additional background option, which determines both an ability score bonus and starting equipment. If meaningful steps are to be taken to address issues of proceduralized whiteness in games then character creation systems may represent one important starting point.

Explore, Extract, Expand, Exterminate: Whiteness as an Embodiment of Colonial Domination

Many games that do not offer character-creation systems can also provide examples of proceduralized whiteness in games, as in the case of what Dyer-Witheford and De Peuter (2009) refer to as games of empire. At the core of their book, Games of Empire: Global Capitalism and Video Games, the authors offer the following central assertion: that “video games are a paradigmatic media of Empire—planetary, militarized hypercapitalism— and of some of the forces presently challenging it.” (p. xv). While I depart from Dyer-Witheford and De Peuter in considering all games through this lens, their argument can still be usefully applied for analyzing one of the core procedural tropes in gaming—a game’s objectives.

As we have established, one the ways that whiteness has been ideologically deployed is as a justification for, and an extension of imperialist invasion and settler-colonial occupation. If we follow the line of Dyer-Witheford and De Peuter’s argument to understand the relationship between games and empire, we can identify some of the ways in which games can serve both the interests of whiteness and those of imperial powers. I use the term “objectives” in this essay to describe the actions a player is meant to take within the playable universe of the game itself, though others have interchangeably referred to these as “goals” (Schell, 2008).

In many popular strategy games under the banner of “4X,” from Sid Meyer’s Civilization (1991) series to Microsoft’s Age of Empires (1997), the overarching objectives of the game center on exploring land, expanding territories, exploiting resources, and exterminating those labeled as enemies. While perhaps seeking to provide a simulation of the alternative history of human society, these and other games simultaneously serve as a site for normalizing, mythologizing, and romanticizing imperial and settler-colonial logics (Hawreliak, 2018). While it is beyond the scope of this paper to discuss more fully, it should also be noted that the notions of exploitation and extermination also track with ideologies of extractive capitalism and class conflict, which are themselves caught up in the mythologization of whiteness (Dyer-Witheford and De Peuter, 2009). Further, while these games may offer a range of cultures and societies to play as, and even a range of victory conditions in the case of Civilization, many of these still center around establishing dominance over others in the world, be it through developing a capacity for interplanetary colonization, establishing a dominant religion, or through sheer military force.

Figure 5: Screenshot of the “Religious Victory” condition in Civilization 6 (2016).

Contrast this, for example, with games in which violent domination is treated quite differently. In role-playing games like Undertale (Fox, 2015), following a path of violence leads to an entirely different play experience and ending than a non-violent play through. In games like Pillars of Eternity (Obsidian Entertainment, 2015), experience points (a measure of character growth), are not simply rewarded for killing everything that moves (as has been a historical trope in WRPGs), but instead through resolving encounters and completing quests through various kinds of in-world problem solving. While combat does feature prominently in Pillars, it is not the only, or even the most viable solution presented for players to accomplish their objectives. Finally, games like Longboat’s (2019) Terra Nova provide an additional glimpse into the possibilities afforded by developing game-based explorations of a “First Contact” story set in the distant future. The brief, two-player platformer centers goals like exploration, cooperation, and survival without necessarily glorifying the goals of the empire or normalizing the logics of white settler-colonialism.

Worldbuilding Whiteness: Relations with the Natural and the Spiritual

As a final example of proceduralized whiteness, I turn from an exploration of a game’s overarching goals, which in turn constrain player actions, to an exploration of the actions themselves—the things a player can do in a game to interact with its world and move toward their objectives. In colloquial discussions, these are sometimes referred to as a game’s “verbs:” actions like moving, running, jumping, flying, shooting, collecting, hiding, swinging a sword—the list of player actions within a game world is bound only by imagination. What I will argue here, however, is that it is in these proceduralized player actions, and even more specifically in the ways they illustrate relationships with a game’s world, that a third dimension of proceduralized whiteness can be identified.

Whiteness can be understood as relational in two senses: firstly, it can only be defined in relation to other racialized categories it has produced and hierarchically organized; secondly, it represents an ideological worldview that defines the relationships that people have with themselves, with other people, and with non-human entities in the world, such as plants, animals, land, and weather. It is this second definition of the relational nature of whiteness that I will focus on here. A game can procedurally embody whiteness in the way it frames the actions a player can take in the world, and thus a player’s relationship with that world.

Baldur’s Gate 3, a WRPG developed by Larian Studios (2020) based on the Dungeons and Dragons 5th Edition Tabletop Ruleset, illustrates this principle. Though BG3 itself is a computer game, it draws largely from the original tabletop reference material, which we can examine to understand the ways that it situates different playable character classes, such as the Barbarian, introduced in the Player’s Handbook in this way:

A tall human tribesman strides through a blizzard, draped in fur and hefting his axe. He laughs as he charges toward the frost giant who dared poach his people’s elk herd.

A half-orc snarls at the latest challenger to her authority over their savage tribe, ready to break his neck with her bare hands as she did to the last six rivals.

Frothing at the mouth, a dwarf slams his helmet into the face of his drow foe, then turns to drive his armored elbow into the gut of another.

These barbarians, different as they might be, are defined by their rage: unbridled, unquenchable, and unthinking fury. More than a mere emotion, their anger is the ferocity of a cornered predator, the unrelenting assault of a storm, the churning turmoil of the sea.

For some, their rage springs from a communion with fierce animal spirits. Others draw from a roiling reservoir of anger at a world full of pain. For every barbarian, rage is a power that fuels not just a battle frenzy but also uncanny reflexes, resilience, and feats of strength.

Characteristic of this framing, as Sturtevant (2021) asserts, is an emphasis on the concepts of “tribe,” “savage,” and a “communion with animal fierce animal spirits,” harkening back once again to racialized depictions of Native and Indigenous Peoples. Rather than simply serving as narrative flair, however, stereotypical tropes are also embedded into the procedural design of the barbarian, specifically in the class’ “communion with fierce animal spirits.” As the handbook continues to describe one possible development pathway of a barbarian character:

The Path of the Totem Warrior is a spiritual journey, as the barbarian accepts a spirit animal as guide, protector, and inspiration. In battle, your totem spirit fills you with supernatural might, adding magical fuel to your barbarian rage.

As Sturtevant (2021) explains, this procedural design misappropriates a particular aspect of the spirituality of certain Native traditions, reframing it through a well-established stereotype in the white settler-colonial imaginary.

As Picotte writes on the “Partnership with Native Americans” blog:

In my teachings, a Spirit Helper isn’t something you choose or identify with but rather something that comes to you in your time of need. Perhaps the animal represents something that holds a certain value, such as strength in a bull or agility in a dragonfly. Lakota culture, it’s from these spirits that we tend to associate values with certain animals. However, that’s not all they bring.

Spirit Helpers are not a novelty. They hold a special place and represent a larger spiritual culture within a tribe. Many people don’t take the time to really understand this, and the adapted understanding and misappropriation is concerning and often offensive to Native cultures. (2018, n.p.)

In designing the barbarian class and narratively framing it in this way, game developers are positioning players in a particular relationship with animals and their spirits: as things to be used, mystical and supernatural forces, and ultimately tools for fueling a violent rage.

In stark contrast is the design of spirit helpers in Upper One Games’ (2014) Never Alone: Kisima Ingitchuna, which was developed in collaboration with Ishmael Hope, a storyteller and poet of Iñupiaq and Tlingit heritage, and the Cook Inlet Tribal Council. For background, Never Alone is a puzzle platform adventure game in which players guide an Iñupiaq girl and her arctic fox companion on a journey to save her village and restore balance to nature. In a presentation at the 2015 Game Developers’ Conference, art director Dima Veryovka revealed that an initial design of spirit helpers in the game involved players switching between the physical world and the spirit world at the touch of a button (GDC, 2017).

Figure 6: A spirit helper in Never Alone (2014) aids the player characters.

However, after tribal members, artists, and storytellers were consulted, the design was replaced with an approach that frames a different kind of relationship between people and the spirit world. In the final design, spirit helpers appear on their own to aid players, though their appearance is unpredictable, procedurally representing the idea that spirits do not exist for summoning and control at will by humans. As Fannie (Kuutuuq) Akpik explains in one of the game’s unlockable Cultural Insights videos:

I think spirit helpers in and of themselves are really about how we’re connected with things. And so it may be that there is a spirit helper that shows themself as a bird to show you the way home. Or it may be a spirit helper that actually decides to show themselves with the face and body of a man instead of their animal form. And so I think one of the things that’s hard to understand is that it’s not one way of seeing things. It’s one way of knowing you’re connected to everything. We’ve always had that spirituality of everything around us. It’s the interaction you have with the air you breathe, the ocean that you gather resources from, the rivers from which you gather fish, the tundra from which you pick berries, the animals that give themselves—it’s all of all of that. (“Sila Has a Soul,” Cultural Insight #6, Upper One Games, 2014)

What is important about this and other cultural insights in the game is how they help players understand their relationship with other entities in the game world, which reflects, in part, Iñupiaq ways of relating to the world. Granted, games like BG3 and other adaptations of the D&D franchise are not necessarily concerned with representing the real world as they seem to be with crafting a fantasy. However, if these fantasies are steeped in the ways that whiteness circumscribes our relationships with ourselves and the world beyond us, then they risk continuing to propagate these ideologies, despite public commitments to design with an eye toward diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Reconfiguring Relations: Proceduralizing the Politics of Resistance and Liberation

Though I have thus far positioned the ideologies of whiteness and indigeneity in videogames in an oppositional framing, I want to be clear that this framing is not meant to suggest that the burden of resistance to and liberation from whiteness should be placed solely on independent and Indigenous game developers. In the article “Precarity and Why Indie Game Developers Can’t Save Us from Racism,” Srauy (2019) demonstrates that when the project to redress representational inequities within games is shifted on to indie developers, we intensify the emotional and cultural labor placed on creators already burdened with the material and social conditions underlying their precarity in the gaming industry, as well as their very existence in the world.

However, as a pre-publication reviewer of this piece has reminded me, tactics for promoting Whiteness at the sites of production, dissemination, and reception of videogames are often intentional (cf. Rose, 2016). It is often framed as time-consuming, expensive, and complicated to hire teams representing diverse racialized identities and cultural knowledges in game development (Srauy, 2019). Further, vocal outrage from a highly toxic minority of players (often white and male) when norms are challenged can pose serious problems to a game or development company’s public relations and economic resources (Kung, 2019). International pressure against more meaningful representation, particular from nations with their own troubled imperialistic legacies, continues to impact creative development choices within and beyond videogames (Huang, 2018).

What I do hope to demonstrate, however, is how Terra Nova (2019), When the Rivers Were Trails (2019), Never Alone (2014), and other Indigenous-centered games offer a glimpse of a purposiveness in game design—intentionality, from early planning to player experience—that directly opposes proceduralized whiteness and does so in two fundamental ways. First, these games embody a politics of resistance (Pickett, 1996) in their intentional subversion the procedural tropes of character creation, conflict resolution, and relationality with the world. In the aesthetic experience of playing these games, the mythological norm of whiteness is disrupted when players are offered ways of being/doing/thinking that go well beyond’ racialized categories, normalized violence, and extractive relationship with the natural and spiritual worlds.

Secondly, in line with their procedural and perceptual design, these games also embody a politics of liberation (Carmichael, Ture, & Hamilton, 1992) in how they configure the social and material relations between their developers and audiences. Terra Nova (2019) represented a solo-developed project by Maize Longboat that carried epistemic weight as part of a thesis project highlighting the contributions of Indigenous developers and gamers, past and present. Never Alone (2014) was developed in partnership with storytellers and poets of Iñupiaq and Tlingit heritage, as well as members of the Cook Inlet Tribal Council, utilized the medium of videogames to share stories, experiences, and cultural insights, and continues to be distributed across independent and popular gaming platforms alike. Finally, When the Rivers Were Trails (2019) featured over thirty Indigenous writers, artists, and musicians, and support from the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians. The centrality of these relations is interwoven throughout the experiences of these games and offers a very different stance of engagement for players seeking to bridge gaps between virtual and material realities.

I close this essay by reissuing the essential reminder by Tuck and Yang (2012): decolonization is not a metaphor. If marginalized peoples are to survive whiteness through a politics of resistance, and if we are to free ourselves from its oppressive structures through a politics of liberation, then we must seek to radically transform the social and material conditions giving rise to the challenges embodied in proceduralized whiteness: settler-colonial occupation, capitalist modes of production, racist systems of social organization, and extractive practices leading to environmental destruction. While Indigenous-centered games can offer us glimpse of the world as it could be, it is the responsibility of all people to do this work of unsettling white supremacy from wherever we stand, to make such a vision our shared reality.

Author biography

Dr. Earl Aguilera is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Curriculum and Instruction at California State University, Fresno. He is a teacher educator and scholar on issues at the intersection of digital literacies, critical pedagogy, and educational justice. He has presented work as part of the Games, Learning, and Society Conference and the Connected Learning Summit. His work as appeared in a variety of educational, technology, and media-related journals.

References

Abercrombie, N., & Turner, B. S. (1978). The dominant ideology thesis. The British Journal of Sociology, 29(2), 149–170.

Ahmed, S. (2012). On being included: Racism and diversity in institutional life. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822395324

Aspyr. (2016). Civilization VI. 2K Games.

Benjamin, R. (2019). Race after technology: Abolitionist tools for the New Jim Code. John Wiley & Sons.

Blizzard Entertainment. (2004). World of Warcraft. Activision Blizzard.

Bogost, I. (2010). Persuasive games: The expressive power of videogames. MIT Press.

Bonilla-Silva, E. (2006). Racism without racists: Color-blind racism and the persistence of racial inequality in the United States. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Carlquist, J. (2013). Playing the story: computer games as a narrative genre. Human IT: Journal for Information Technology Studies as a Human Science, 6(3). https://ojs.bib.hb.se/index.php/humanit/article/viewFile/144/148

Carmichael, S., Ture, K., & Hamilton, C. V. (1992). Black power: The politics of liberation in America. Vintage.

Collins, P. H. (2002). Black Feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. Routledge.

de Roock, R. S. (2021). On the material consequences of (digital) literacy: Digital writing with, for, and against racial capitalism. Theory Into Practice, 60(2), 183-193.

Dunbar-Ortiz, R. (2014). An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States. Beacon Press.

Dyer-Witheford, N., & De Peuter, G. (2009). Games of empire: Global capitalism and video games. University of Minnesota Press.

Respawn Entertainment, Panic Button Games. (2019). Apex Legends. Electronic Arts.

Eubanks, V. (2018). Automating inequality: How high-tech tools profile, police, and punish the Poor. St. Martin’s Publishing Group.

Frankenburg, R. (1993). White women, race matters: The social construction of whiteness. Routledge.

Fox, T. (2015). Undertale.

Gee, J. P. (2007). What video games have to teach us about learning and literacy (2nd Ed.). St. Martin’s Press.

Hall, S. (1986). The problem of ideology—Marxism without guarantees. The Journal of Communication Inquiry, 10(2), 28–44.

Hawreliak, J. (2018). Multimodal semiotics and rhetoric in videogames. Routledge.

Henry, F., & Tator, C. (2006). The colour of democracy: Racism in Canadian society (3rd ed.). Thomson Nelson.

Huang, E. (2018). ‘A Torture for the Eyes:’ Chinese Moviegoers Think Black Panther Is Just Too Black. Quartz. Available: https://qz.com/1226449/a-torture-for-the-eyes-chinese-moviegoers-think-black-panther-is-too-black/

Johnson, J. (2021, May 2). “She got game: How Black Girl Gamers Are Winning Online.” Slate. https://slate.com/culture/2021/05/black-women-video-games-twitch-storymodebae.html

Kivel, P. (2011). Uprooting racism: How white people can work for racial justice (3rd Ed.). New Society Publishers.

Kung, J. (2019, August 31). Should Your Avatar’s Skin Match Yours? NPR. https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2019/08/31/430057317/should-your-avatars-skin-match-yours

LaPensée, E. (2019). When the Rivers Were Trails. Elizabeth LaPensée, Indian Land Tenure Foundation, Michigan State University GEL Lab.

Larian Studios. (1998). Baldur’s Gate. Larian Studios, Beamdog, Interplay Entertainment, MORE.

Larian Studios. (2014). Divinity: Original Sin. Larian Studios, Focus Entertainment.

Larian Studios. (2020). Baldur’s Gate III.

Leonard, D.J. (2007). “Performing Blackness: Sports, Video Games, Minstrelsy, and Becoming the Other in an Era of White Supremacy,” in M. Flanagan and A. Booth, (Eds.)., Re: Skin, pp. 321–339, MIT Press.

Levine-Rasky, C. (2012). Working through whiteness: International perspectives. SUNY Press.

Lin, B. (2021, August 4). Diversity in Gaming: An Analysis of Video Game Characters. Diamond Lobby. Available: https://diamondlobby.com/geeky-stuff/diversity-in-gaming/

Longboat, M. (2019). Terra Nova: Enacting videogame development through Indigenous-led creation [Masters, Concordia University]. https://spectrum.library.concordia.ca/985763/

Lorde, A. (2012). Sister outsider: Essays and speeches. Clarkson Potter/Ten Speed. (Original work published 1984)

Marshall, C. (2020, June 23). Wizards of the Coast is addressing racist stereotypes in Dungeons & Dragons. Polygon. Available: https://www.polygon.com/2020/6/23/21300653/dungeons-dragons-racial-stereotypes-wizards-of-the-coast-drow-orcs-curse-of-strahd

Meier, S. (1991). Civilization. 2K Games, Firaxis Games, Aspyr, MicroProse, MORE.

Microsoft Game Studios. (2007). Mass Effect.

Microsoft Corporation. (1997). Age of Empires. Microsoft Corporation, Xbox Game Studios, MacPLay, MacSoft.

Minnesota Educational Computing Consortium. (1974). The Oregon Trail. MECC, Gameloft, The Learning Company, MORE.

Murray, J. H. (2017). Hamlet on the Holodeck: The future of narrative in cyberspace (2nd Ed.). MIT Press.

Murray, S. (2018). Video games and playable media. Feminist Media Histories, 4(2), 214–219.

Noble, S. U. (2018). Algorithms of oppression: How search engines reinforce racism. NYU Press.

Obsidian Entertainment. (2015). Pillars of Eternity. Versus Evil, Paradox Interactive.

Picotte, T. (2018, October 16). Storytelling in Native American cultures. Partnership with Native Americans. http://blog.nativepartnership.org/storytelling-in-native-american-cultures/

Rose, G. (2016). Visual methodologies: An introduction to researching with visual materials. Sage.

Schell, J. (2008). The Art of Game Design: A book of lenses. CRC Press.

Srauy, S. (2019). Precarity and why indie game developers can’t save us from racism. Television & New Media, 20(8), 802–812.

Sturtevant, P. (2017). Race: the Original Sin of the Fantasy Genre. The Public Medievalist. https://www.publicmedievalist.com/race-fantasy-genre/

Sturtevant, P. (2021, March 18). Improving Dungeons and Dragons: Racism and the “Barbarian.” The Public Medievalist. https://www.publicmedievalist.com/dungeons-dragons-racism-barbarian/

TallBear, K. (2003). DNA, blood, and racializing the tribe. Wicazo Sa Review, 18(1), 81–107.

Tuck, E., & Yang, K. W. (2012). Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 1(1), 1–40.

United States Army. (2002). America’s Army. Ubisoft, United States Army.

Upper One Games. (2014). Never Alone. E-Line Media.

Vidakis, N., Christinaki, E., Serafimidis, I., & Triantafyllidis, G. (2014). Combining Ludology and Narratology in an Open Authorable Framework for Educational Games for Children: the Scenario of Teaching Preschoolers with Autism Diagnosis. Universal Access in Human-Computer Interaction. Universal Access to Information and Knowledge, 626–636.

Wardrip-Fruin, N. (2020). How Pac-Man Eats. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Zimmerman, E., & Salen, K. (2003). Rules of play: Game design fundamentals. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.