by Matthew Jungsuk Howard

First published January 2022

Download full article PDF here.

Abstract

The StarCraft II Visual Novel (2015; SC2VN) is a fish-out-of-water story following a white, nominally North American or European, StarCraft II (2010; SC2) player who goes to South Korea to try and make it as a professional gamer in the world’s most competitive country for SC2 play. While the course of the novel investigates the resonant mental battles of trying to turn your favorite video game into your job and the precarity of professional gaming in the mid-2010s, the game’s setting choices and aesthetic design reveal an embeddedness in Western techno-Orientalist discourses surrounding Korean esports’ success in international play. SC2VN attempts to re-humanize Korean players through its characters and story, but it does so with set pieces that fall back on techno-Orientalist tropes that make esports’ Koreanness recognizable and sensible to a presumed Western audience through specific arrangements of bodies, technologies, and places. By analyzing the aesthetics and deployment of the game’s most frequent setting, this paper historically situates the SC2VN and examines techno-Orientalism and high-tech Orientalism’s manifestations in the game’s setting and narrative, outlining both Whiteness’s influence over esports discourses and its processual re-orientation to the perpetuation of its own privilege there. The result is an essentialized Koreanness in esports contexts that has epistemic effects on Korean/American subjectivation.

The StarCraft 2 Visual Novel’s (Team ElevenEleven, 2015) full title line on Steam—Valve Corp’s digital game sales and social management platform—is, “SC2VN—The Esports Visual Novel.” When this game was released, I remember being ecstatic because I was not familiar with any other works of fiction that dealt directly with esports subject matter. Playing SC2VN made me feel seen, especially as a North American esports fan trying to figure out why my favorite teams and players were being waxed by South Korean opponents in international play. Looking back, six years later, my perspective has changed. The game asks the same question I grappled with in my fandom, but it looked at South Korean esports much the same way I looked at my own Koreanness back then. As a multiracial Korean/American, I had the privilege of often passing White. By orienting myself in that way, I could sink into my surroundings, and many subjective possibilities seemed reachable (Ahmed, 2007). However, others, like my own Koreanness, seemed foreign and far from my fingertips. Now that I identify more fully as multiracial Korean/American, the SC2VN is a messier cultural knot that I want to start untangling.

This paper intervenes in existing Esports Studies literature by examining an esports research object through an Asian/Americanist critique. The SC2VN—produced and written by Americans but premised on cross-cultural encounters with South Korean Others—presents an expression of North American imaginations of the Korean Gamer in esports spaces, where video games are more than play; they are professions.

Examining objects like the SC2VN is important to both Asian/American and Esports Studies because of the role Korean imaginaries have played and continue to play in cultural discourses around esports (Choe & Kim, 2015; Bae, 2021; Voorhees & Howard, 2021). When the SC2VN came out, South Korean teams had won consecutive League of Legends World Championships and come second in a third contest. In StarCraft: Brood War (1998) and StarCraft II: Wings of Liberty (2010) esports both, South Korean players had taken more prize earnings than the rest of the world’s professional players combined (E-Sports Earnings, 2015a; E-Sports Earnings. 2015b). Due to the height of South Korean esports successes and Western gaming’s imagined underdog quest to defeat ambivalently respected and feared Korean overlords (Zhu, 2018, p. 229), the question is: What web of cultural tensions do Korean/Americans have to grow up with and survive? Specifically, if we recognize the cultural importance of both digital gaming and esports as pastimes in the U.S., then we must also grapple with their implication: Esports discourses, and their attendant fictionalized expressions like the SC2VN are brush strokes on the larger racial and cultural mural against which Korean/American lives happen.

The American esports mural is the cultural landscape within and beholden to which processes of Asian and Korean/American racialization happen. Questions of representation, participation, and imagination play both active and passive roles in the development of racialization processes and the ways in which race is produced systemically, partaken of culturally, and done to people. It is, particularly in the Asian/American case, the consensus of intersecting Orientalist, racist, anti-racist, gendered, and other identity-based knowledges. The SC2VN simultaneously expresses this mural and adds to it by engaging with public esports discourses about South Korean esports dominance and offering its own imagination of esports cross-cultural encounter between West and East through a fish-out-of-water adventure story. It is an epistemic expression—of and affecting ways of knowing the world—and produces epistemic effects because it is woven into the historical fabric of 2010s esports. I am therefore concerned with its relationship to Koreanness in North American esports cultures and racialization processes.

I define Koreanness as an epistemic subjectivation process that occurs within the tension points between the individual subject and the cultural environment imposed upon them. The latter is an essentialized standard of Koreanness I see similarly to Foucault’s (1969) archive—a set of unspoken assumptions, conventions, and knowledges governing discourse (pp. 145–146). It is a set of socio-cultural identity standards about what being Korean should look, sound, and behave like that are done to individual Korean subjectivities. Koreanness is the fundamental incomplete resemblance between someone’s individual sense of being Korean and the verbing of standards set for them by the world they live in.

Describing this subjectivation process as “-ness” distances the ways Korean/Americans navigate White Supremacist, settler-colonial societies in North America from any fundamental inherencies of national or ethnic identity in contexts of globalization (Wiley, 2004, p. 91). Instead, Koreanness posits Korean/American subjectivation as a subjectless process (Chuh, 2003, pp. 10–11), affording and limiting emergent subjectivities systemically through socio-cultural and racial norms under constant, plural revision rather than directly producing them. On the peninsula, this process is revealed by the contemporary discursive constructions of multiethnic South Korean nationality through an articulation of race, nation, and media, where context-dependent epistemic projects perpetuate a neoliberal form of multiculturalism that individual Korean identification is measured against (Ahn, 2018, pp. 35–36). Articulations like this one embody Wiley, Sutko, and Moreno’s (2013) assertion that subjectivation happens in relation to assemblages (of media, infrastructure, transportation, etc.) that link people to differing senses of social space, globalization, and identity (p. 367). Individual Korean/American subjectivities, then, should be understood as developing against the backdrop of essentialized Koreanness, such as the peninsular race-nation-media articulation, or North American racializations based on labor exclusion at borders (Day, 2016, pp. 33–34) & ludo-Orientalism’s construction of Asianness as both allergic to fun and essentially inclined toward gambling and gaming (Fickle, 2018, pp. 3–4). The SC2VN participates in Koreanness as a part of an esports media and discourse-based construction of essentialized Koreanness specific to that space, but that is informed by existing processes of racialization both in and beyond esports. There are no static actors here; players consume media and carry parts of it with them. My research question, then, is: Where is the Koreanness in this game and how is it (re)presented?

The SC2VN works hard to re-humanize Korean players whose play styles and widespread success have been characterized as part of an industrial system, but the game falls victim to the discourses it participates in. This industrialized, machinic depiction of South Korea’s esports industries is revealed in Western pundit and fan discourses that essentialize Koreanness as both the producer, product, and literate consumer of esports technologies, whose hyper-technologization looms darkly over the future of a White neoliberal monopoly on modernity (Voorhees & Howard, 2021). This often appears as determinist views on Korean esports success and the depiction of Korean teams as fully-integrated machines smoothly and noiselessly producing international dominance that could not be reproduced by simply “importing” Korean “parts” (Shields, 2014, 2015; Erzberger, 2016). The SC2VN’s final product, however, only accomplishes this counterargument in a limited way because it never escapes the techno-cultural Othering discourses it argues against. This is illustrated particularly in the game’s marrying of setting and aesthetics. While each of the SC2VN’s Korean characters feels deeply human, what does it mean that the game mostly takes place in a gaming-focused pc bang—an internet cafe filled with gaming computers?

Contrary to the more individualized gaming setups common to North America and Europe, the pc bang and its attendant link to essentialized Koreanness mark it as a space where, not esports, but Korean esports happens in North American popular discourses (Mozur, 2014; Maiberg, 2015; John K., 2020) [1] . By locating a knowledge of cultural production in the pc bang, however, esports discussants, especially in North America and Europe, have reiterated an old rhetorical move that renders Asian Others most knowable through their relationships with technology, and such technologies as the site of intercultural interaction in a globalizing world. This is a reiteration of what postcolonial scholars have called techno-Orientalism (Morley & Robins, 1995; Ueno, 2002; Roh, et al., 2015).

Through the SC2VN’s setting and aesthetic design, GZ becomes a racial-cultural womb. Korean birth/self-actualization is largely set in a room full of computers that facilitates Korean sociality. Playing as a White, Western avatar, we are shown this space where Koreanness happens, encouraged to use it to become more Korean, and aspire to leave it as a Korean esports pro. Effectively, the game participates in high-tech Orientalism (Chun, 2011, pp. 50–51) and datafies essentialized Asian subjectivity for Western consumption/appropriation against a future hostile to Whiteness. Thus, while it does the work of making Korean players less industrial, technological, and machinic through its character development, the design choice to anchor this narrative in Golden Zonefire as a knowable, accessible, and conquerable setting renders Koreanness knowable, accessible, and conquerable, reiterating the historical Western desire to force Asia open for Western economic gain. Korean/American subjectivation is caught between the two worlds SC2VN crashes together, but it is not directly represented.

To map out the game’s complicated relationship with Whiteness, Asian, and Asian/American racializations, I’ll begin with a brief overview of the game’s plot, characters, and themes. Afterward, I will lay out scholarly conversations surrounding the intersections of digital games, aesthetic design, and space, as well as theories of Orientalism relevant to this traveler’s tale. I will then outline its historical grounding in esports discourses and the racialization of Korean esports players that maps the contours of essentialized Koreanness in North American esports cultures. Finally, I will describe and discuss the aesthetics of Golden Zonefire and its mediation of the story that plays out on it, before concluding with a discussion of SC2VN and essentialized Koreanness’s relevance to Korean/American subjectivation.

Overview of the StarCraft II Visual Novel

The SC2VN started out as a joke YouTube video (Maiberg, 2015; Vogue kun, 2013). Then it became a Kickstarter, where the creators, Team Eleven Eleven, received $8,370 to make the game (Huckabee, 2016). It launched in September of 2015, Free-to-Play. The game repeatedly questions the circumstances that make great esports players and who people become under adversity. Its story begins with Mach at their lowest low. SC2VN follows Mach, a skilled, white-presenting, English-speaking StarCraft II (Blizzard Entertainment, 2010) enthusiast who skips college and moves to South Korea for a couple of months using summer job savings and some money from their grandparents. Their aim is to become a professional player in SC2’s most competitive region. After failing to qualify for the solo professional league, Mach meets professional players by chance at a pc bang, recruits misfit teammates, and eventually qualifies for the Korean professional StarCraft II team league, thus achieving their dream by game’s end. Mach is initially rejected by Koreans as a foreigner and battles their own feelings of isolation, learns to overcome their anxieties, and earns the respect of those Koreans who rejected them initially.

Figure 1: Gender Selection menu for Mach in the StarCraft II Visual Novel. Screenshot taken by the author.

Two of the game’s creators, Young and Huckabee, stated that the developers wanted to pay special attention to broadly applicable tensions and conflicts that arose in esports contexts, such as those between Western foreigners and Koreans, sponsors & players, and online vs. offline identities (Stickney, 2015). The creators had initially aimed to build the SC2VN out of an alternate Earth, where women were given opportunities without as much resistance from communities and structures around them, but they felt this would be erasive and decided to tackle some of those social issues in the game’s text (Khaw, 2015). Based on these attestations, I think it fair to allow that Huckabee and Young were interested in an activist mission within their desire to tell an esports story. The SC2VN was, awkwardly, striving for a feminist bent on esports discourse at the time and offered some possibilities for what esports could look like socio-culturally with even small adjustments.

Method: Place and Reflective Analysis of Discursive Constituation

The research work for this project was conducted over the course of three months through a critical playthrough of the SC2VN. My interest in the importance of Golden Zonefire emerged due to its primacy among the game’s settings. Accordingly, this paper examines this setting choice and its aesthetic design as game design decisions that express Western imaginations of Koreanness.

Decisions about what is sensible to render sense-able on a small-budget game are a key critical site. Aesthetic inquiry of these decisions can recognize the epistemic effects of liberal-humanist Whiteness’s quest for access and essentialisms. As argued by Chuh (2019), aesthetic inquiry investigates the ways that the perceptible yields kinds of knowledge as expressions of power relations:

As a method, aesthetic inquiry insists that we acknowledge a dialectical relationship between liberal and illiberal humanisms…aesthetic inquiry emphasizes sensibility as a crucial domain of knowledge and politics; it affords recognition of both the relations and practices of power that legitimate and neutralize certain ideas over others, and the knowledge and ways of living subjugated or disavowed in the process. (p. 3)

SC2VN’s aesthetic design choices should be scrutinized, then, for they mediate epistemic expressions within the constraints of the visual novel game. Golden Zonefire’s design had to make sense to both the designers and their imagined audiences, and that sense-making process tackled the economic quandary of portraying Korea through a legible or sensible Koreanness on a budget. Essentialized Koreanness happens in game design through processes of semiotic efficiency.

The game shows Koreanness through its setting choices. It provides spatial settings that have a sensibly Korean placeness to them for an audience assumed to be Western, English-speaking, and literate in esports discourses about Korean dominance and Western frustration. Drawing on scholarship that interrogates the spatial settings and cultural-historical architectures of video games (Seif El Nasr et al., 2008; Murray, 2017), this paper considers SC2VN’s pc bang portrayals as culturally and historically-situated discursive contributions. They are epistemic expressions and projects simultaneously that doubly affect—both imitating and revising—Koreanness in North American esports cultures.

In North American esports cultures, essentialized Koreanness is what Patterson (2020) would call, Asiatic, or “…a style or form recognized as Asianish but that remains adaptable, fluid, and outside of the authentic/inauthentic binary…As virtual, the Asiatic does not strive for realness but plays upon the real” (p. 27). In the SC2VN, the representations of South Korea are built in ways that Western imaginations recognize as Korean-ish, playing upon the dominance of South Korean StarCraft and League players, as well as the myriad ways North American and European pundits explained it (Howard, 2018, p. 47; Zhu, 2018, p. 229). The driving conceit of this paper is that contributions to an Asiatic essentialized Koreanness serving White supremacy, like the one present in the SC2VN, are an essential part of how Korean/Americans live and grow up.

Existing digital game studies scholarship has argued the historical and socio-cultural significance of video game aesthetics and design. Murray stated that the form and aesthetics of design are historically situated, using Assassin’s Creed III: Liberation’s (Ubisoft, 2012) historical proximity to GamerGate as an example. For Murray (2017), “…a politics of identity is present in the form of the game as well as its content” (p. 80). A decade earlier, Seif El Nasr et al. (2008) argued that architectural design played key roles in constructing senses of fun in play experiences while also indicating that play itself is plurally and culturally situated (p. 4).

Given these and Dyer-Witherford and De Peuter’s (2009) argument that the design of in-game urban spaces reproduces dominant relations of power (pp. 156–157), my analysis focuses on the ways that GZ is culturally and historically-situated in such relations. I ask what it means to set an esports fish-out-of-water story in South Korea, the importance of one primary set piece’s being a cafe filled with gaming computers, and how the characters’ actions within that designed space can be understood critically and historically, with an eye toward racializations of the Korean Other and the White, Western main character in relation to essentialized Koreanness.

This analysis is founded on Ahmed’s (2007) assertion that Whiteness is a default orientation that assumes Othered bodies’ failure to fit (p. 153). Whiteness is an orientation that inherits a historical landscape of reachable objects, physical or otherwise. In a world where colonialism has endeavored to situate Whiteness as the default orientation, Whiteness recognizes and becomes uncomfortable with differences that disorient it (pp. 163–164). Ahmed points out that the rhetorical discursive power of Whiteness’s orientation lies in the disavowal of its own advantages (p. 163). Whiteness points to the achievements of Othered bodies as evidence that the default is accessible to those who deviate from it, and thus reinforces uncritical Whiteness through multicultural narratives (Chuh, 2003, p. 6; Ahmed, 2007, p. 154). Within this framework, all forms of success feel reachable for White orientations, and Others achieving different kinds of success brings those forms to White attention, of course, with assumed reachability.

Orientalist narratives, then, can be considered means of White colonization whereby the desirable aspects and achievements of Others are made attainable and obtainable. Ahmed’s (2007) Whiteness orientation leans on the idea of discomfort, but in some Orientalist cases, this sharply manifests as fear. Techno-Orientalist frameworks conceive of a global future state in which Whiteness has become obsolete as hyper-modern and over-technologized Asian Others surpass Whiteness as the ideal neoliberal subject position (Roh et al., 2015, pp. 2–3). As a shadow of late-imperial White subjectivity’s internal struggle with a sense of growing obsolescence, techno-Orientalism points to technologies as the new sites of cross-cultural interaction and Asian bodies as closer, and more willingly subservient, to technologies, which are conceived as the primary trappings of modernity (Roh et al., 2015, pp. 2–3). The Asian body is Othered in this imagination as dehumanized, willing to compromise its mortal coil for machinic and corporate interest, and thus more readily able to create a neoliberal future to the detriment of White liberal-humanist subjecthood (Choe & Kim, 2015, pp. 114–115).

Building on this scholarship, Chun (2011) argued for a particular form of techno-Orientalism named high-tech Orientalism. Its argues that an Asian future might be subverted, prevented, or survived through the datafication of Asian subjectivities, such that White bodies might partake of a selective form of identity tourism and passing (p. 51). By reducing racial subject positions to specific, concrete data, Whiteness might regain control of or prevent the techno-Orientalist future by passing essentially Asian “enough” to regain Whiteness’s central neoliberal subject position (p. 50). Effectively, high-tech Orientalism states that White people can regain their default orientation status by identifying the traits of the Other (all of which are assumed reachable) that are desirable but leaving room for their White liberal humanism to “breathe.”

The exercise of Whiteness in high-tech Orientalist contexts, then, is a cyclical, fear-based feeding frenzy on the body of the Other. If the future appears hostile to White subjecthood in the techno-Orientalist view—a canonical, monolithic future for White subjecthood—then the means of preventing that future is what hooks (1992) referred to as “Eating the Other.” hooks argued that White preference for nonwhite sexual relationships was motivated by deviance from a canonical norm of Whiteness (p. 369). She also asserted that the White imagination of racial Others is less of Other humans than of repositories or archives of life experiences inaccessible to the canonical White norm. By communing with these archives, the White subject renders these experiences reachable and accesses a life-sustaining, deviant form of Whiteness that escapes the racial canon and eradicates difference (p. 373). Eating the Other offers something similar to high-tech Orientalism: an escape from a hostile future for White subjectivation by identifying and devouring aspects of the Asian body to reset the default orientation again.

Aesthetics plays a key role in high-tech Orientalist media. High-tech Orientalism holds the promise of learning and pleasurable overwhelmedness that compensates for lacking mastery of the technologies around the Western subject. It steers the self, “…by making it unrepresentable and reducing everything else to images or locations” (Chun, 2011, p. 50). This emphasis on images and locations recalls Said’s (1979) point that Orientalism’s epistemic specificity is anchored in idiom and representation (p. 203). Visual idiom and representation play the essential role of mapping out the datafied Asian subject position for White consumption in a high-tech Orientalist context. Thus, a high-tech Orientalist lens recalls aesthetic inquiry’s emphasis on images as epistemic representations of power relations. Because the game takes place in a historical context inundated with South Korea’s widespread esports success, set art like Golden Zonefire’s was conceived (not necessarily critically) in relation to White fears of an encroaching techno-Orientalist future-present in esports and debates over how to eat the Korean Other (Voorhees & Howard, 2021).

Analyzing Whiteness and essentialized Koreanness through Golden Zonefire reveals the way the SC2VN uses that setting and Mach’s ability to enter it and partake of it to reset their subject orientation to a position of Whiteness. That is, by entering an epistemically essentialized space for Korean techno-cultural and industrial production, Mach is able to commune with the Other, access the life experiences contained in the Other’s body and sociality, and become an unquestioned part of a greater Korean whole. Mach is rebirthed as Korean enough to reset difference to an externality and once again look outward from their White body. By silencing the haters, who would point to Mach’s foreignness before their skill, Mach has reasserted a White, liberal-humanist, multicultural default, where racial and geographic origins are no longer an orientation, but a recognized difference from a White subject position. Mach’s relationship to the pc bang and its aesthetics, then, must both express an essentialized vision of Koreanness and offer additions or revisions to it by delineating Koreanness through essentialized difference essential for esports subjecthood. There is, in SC2VN’s design, an argument about the best kind of Koreanness, and such media offerings shape the tension between Korean/American individual Koreanness and the standards against which they can be measured.

Minding the Gap: The SC2VN’s Historical Intervention

Golden Zonefire’s role is embedded in a context of transnational esports play and Western discourses about the overwhelming dominance of South Korean players and teams. Its historical significance lies in the ways that the pc bang shaped Western esports subjectivities in the mid-2010s as an exotic techno-fantasy. The SC2VN’s depiction of Golden Zonefire and the forms of Koreanness within it are part and product of a larger apparatus that produces essentialized Koreanness in Western esports.

During this historical moment, Korean bodies—but not necessarily Asian/American bodies—were seen as a threat to the West and, accordingly, to esports as a whole. In his book, Good Luck, Have Fun: The Rise of Esport (2016), journalist Li (2016) wrote that, “The dominance of South Korean players became a large problem in StarCraft, creating a repetitive narrative where, with a few rare exceptions, Western players didn’t have a chance of winning” (p. 126). Li argued that South Korean StarCraft: Brood War players would often leave the peninsula and compete in other regional leagues, and they were largely successful in their new homes. Without the regulation of flowing Asian labor that Day (2016) argued is central to settler-colonial capitalism’s racialization of the Asian Other (pp. 33–34), Western fans, journalists, and pundits responded with increasing concern over what they saw as the strangulation of their esports by a foreign menace.

“The Gap” between East and West—what Zhu (2018) called “ethnic antagonism veiled as nationalism” (p. 230)—grew from these insecurities to become the defining Western esports question of the 2010s. Most publicly playing out in League of Legends, the gap described Western esports teams’ continued failures to defeat their South Korean rivals. By SC2VN’s launch in September, 2015, South Koreans were the acknowledged gods of StarCraft and StarCraft II, and they had a fearsome reputation in LoL built on a near-unblemished record of international play against North American and European teams. According to Shields (2015), an esports journalist, broadcast host, and content creator [2] , South Korean teams in League of Legends had, as of January, 2015, won twelve of seventeen international tournaments they had participated in, including consecutive World Championship titles. Team SoloMid, one of North America’s most successful and storied esports organizations had never beaten a Korean team in a best-of series in three years. The gap was an expression of Western anxieties that this portended a techno-Orientalist future that had to be prevented.

Following high-tech Orientalism’s commitment to understanding the racial Other through data, images, and representations, the Gap’s Western discourse in the mid-2010s isolated cultural, economic, and technological inherencies that made South Korean esports better than the West, producing an esports high-tech Orientalism (Voorhees & Howard, 2021). Western pundits blamed both infrastructures and inherent cultural characteristics for North American and European esports failures, engendering a sense of White, Western obsolescence and stirring discussants to a late-imperial neurotic frenzy (Leesman, 2016; Shields, 2016; Erzberger, 2016; Bury, 2017). These pundits, discussion board commenters, and journalists produced tropes that made Koreanness knowable in the West (Bae, 2021, p. 218). In the light of the “South Korean Exodus” in 2014, which saw almost a third of South Korea’s pro LoL talent leave for international contracts (Deesing, 2014; jreece, 2015; theScore esports, 2018b), the League’s developer, Riot Games, implemented interregional labor restrictions preventing teams from fielding more than two “foreigners” (Riot Games, 2015). Blizzard Entertainment, StarCraft: Brood War and StarCraft II’s developer, followed suit, requiring players to have legal residency in the region in which they competed for the StarCraft II World Championship Series (WCS) in 2014 (Blizzard Esports, 2014). The Gap’s historical importance became institutionalized, and, even if the SC2VN was set in a time before such restrictions, the game was developed during this frenzy.

Anti-Asian racisms couched in “threatened” Western labor markets are not new, particularly when read through “cuts” (Boluk & Lemieux, 2017, p. 208) that limit gameplay to what can be quantified, measured, and compared—wins, titles, prize money, and the like. This esports fear is rooted in the racialization of Asian bodies through their relationship with labor, which have manifested in gaming contexts through the construal of gold farmers in World of Warcraft as both disrespecting the game and inherently Chinese (Fickle, 2021, p. 7). In broader historical contexts, the United States’ Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the murder of Vincent Chin, and frequent Asian villains in cyberpunk literature, public discourses, and film have historically revealed these labor-based racisms. According to Day (2016), “Asians represented an alien labor force that mixed with Indigenous land to transform it into white property and capital…the vicissitudes of Asian racialization are primarily shaped by the evolving economic landscape of settler colonialism within a global economy” (p. 31). Day further argued that Asian racialization in North America followed a logic of exclusion, whereby Asian bodies were always already excluded from North America, and political borders acted as semi-permeable management barriers that could select the kinds of bodies demanded by settler-colonial capitalism (pp. 33–34). Both Riot Games’ and Blizzard’s rule changes for their leagues and Chinese exclusion follow this logic by excluding and managing Asian bodies as threats to Western labor. The threatening economic productivity of Asian bodies has long been imagined as a threat to a White, Western-centric future (Roh et al., 2015, p. 11). What Western esports’ cultures’ fears of Korean dominance illustrate, then, is a reiteration of techno-Orientalist discourses derived from Western fears about being overtaken by an Asian Other (Roh et al., 2015, p. 5), which also express a growing rhetoric of White male injury at the hands of women, people of color, and non-straight sexualities (Carroll, 2011, p. 6).

Machinic assemblages of Asian Body and Computer, then, became Western esports’ Baba Yaga. One pundit laid out the Western esports struggle like an absurd dad-history documentary: “Outnumbered and outperformed, the Americans’ numbers dwindled. Within few weeks the name “WCS America” was thick with the same irony that once plagued NASL” (Kolev, 2013). Accordingly, the SC2VN was produced by and operated within contexts of White male fears about globalization and techno-Orientalist futures, and its story intervenes in those conversations, purposefully or not, because the game’s developers specifically aimed to address esports’ effects on people, and their orientations to that goal and historical inheritance govern the knowledges and design archetypes that they saw as reachable (Ahmed, 2007, p. 154).

Techno-Orientalism’s subjectivation question leans on the Western subject’s economic precarity in the face of an Eastern Other’s ability to interface with machines and perform machinic labor. It is the Western subject’s liberal humanism that prevents them from competing on equal footing with the too-modern Other, as the key to Asian economic productivity is tied to a willingness to subordinate oneself to the industrial and technical machines that mark modernity. The great threat of various techno-Orientalisms, then, has been the threat of a future where the liberal Western subject is “…colonized, mechanized, and instrumentalized in its own pursuit of technological dominance” (Roh et al., 2015, p. 4, 11). The SC2VN’s emphasis on Korean spaces, Korean labor practices, and Korean cultural mentalities toward aspiration draw on elements of this Asian racialization within esports contexts to construct an essentialized Koreanness. Mach learns to work like a Korean, which relays a Koreanness of labor to audiences, not so much as a direct injection of knowledge, but as a contribution to an epistemic environment. The high-tech Orientalist deviance from normative Whiteness in the SC2VN occurs as Mach learns to manage their humanity to allow for Korean work, but many pundits argued that these labor conditions were untenable in the West. Enter the pc bang as the emblem of Korean Body-Computer-Infrastructure assemblages.

PC bang are a key factor that Western discussants credit for South Korean dominance in esports (theScore esports, 2018a). But on a more basic level, English language content on YouTube (including a clip from CONAN), present the pc bang as a quintessentially Korean destination, frequently treating the quality of the computer hardware (Today on the Korean Server, 2016), the ability to order food while gaming (Team Coco, 2016), and pc bang’s status as social hubs (Wei, 2015; LoL Esports, 2018) with a mystical exoticism of spaces fundamentally non-Western. Apartments, bars, and even the spectator seating at esports matches are all locations that are not seen as inherently Korean, but pc bang are key epistemic sites for generating essentialized Koreanness. Just as fighting game community members lauded legendary Japanese arcades that even top Western pros stood no chance of conquering (Harper, 2013, pp. 113–115), the pc bang exists in Western esports mythology as an inaccessible, techno-fantasy space where a level of technological interfacing impossible for Western players growing up playing on family computers gets manufactured. The pc bang represents growing up in South Korea, and the warmth of Golden Zonefire is like an energy of opportunity and possibility, because Mach has the chance to try and enter that manufactory. Mach can reject the West that rejected them, and by playing games at Golden Zonefire, grow up Korean. The pc bang becomes more than a birthplace: it is a womb.

The pc bang—literally translated as PC Room—is an established staple of Korean social, technical, and economic spatiality. They boomed in the wake of the 1997 IMF Crisis, South Korea’s most devastating economic recession in recent memory (Jin, 2020, p. 3733), and now pc bang serve many digital activities, ranging from Internet access, online gaming, chat, e-mail, and online dating, as well as conventionally “analog” social functions as meeting hubs for Korean youth or cheap temporary shelters (Chee, 2012, p. 102). These social functions define the pc bang’s role in a broader Korean culture supported by a skeleton of bang-style gathering spaces like pc bang, DVD bang (DVD viewing rooms), or nore bang (karaoke rooms) that are simultaneously specific to certain thematic purposes and versatile to the needs of particular clients (Choi et al., 2009, pp. 135–136). Scholarly discourses maintain that the pc bang is thus both a staple of Korean gaming and an infrastructure for youth socialization, where South Korean young people simultaneously engage with each other and escape from the social pressures, cultural expectations, and poor economic prospects that come with being young in “Hell Joseon” (Stewart & Choi, 2003; Chee, 2006; Huhh, 2008; Choi et al., 2009; Jin, 2010; Chee, 2012; Jin, 2020).

In popular consumer esports discourses, pc bang are portrayed as the origin point of Korean esports dominance and as a primary immersion site for Korean youths in Korean gaming (Mozur, 2014; Maiberg, 2015; J. K., 2020). In fact, some of these writers situate pc bang as the origin point of esports overall, positioning them as the local spaces that made games popular enough to draw in corporate sponsorships (Miller, 2020). In its 2018 World Championship promo material, League of Legends developer Riot Games included a feature called A Korean Pro’s Journey that begins with a Korean pro player discussing entering a pc bang as, “…like finding an oasis in a desert” (LoL Esports, 2018), simultaneously feeding a growing esports legend around pc bang and echoing the findings of scholarly work establishing them as key sites of youth culture and sociality. Mike Sepso, one of Major League Gaming’s co-founders, told Dot Esports that he has, “…really been looking for a way for over a decade and a half to take that magic from early pc bangs in South Korea and look for a way to make that model work in the West” (Miller, 2020). The pc bang’s importance to Korean gaming and esports cannot be underestimated, but these popular discourses position pc bang as the mythological birthplace of esports—simultaneously essential structures of the past infused with arcane mystery and sites of envy and jealousy for Western esports ecosystems that have failed to match South Korean successes on international stages.

The difference between these two threads is teleological: scholarly discourse tends to ask who goes to pc bang and why, enquiring after the social, technical, and cultural logics at play in pc bang attendance and importance. Public esports discourses, meanwhile, tend to assume the inevitability of the current mythology and work backward, situating the pc bang as esports’ birthplace and the MacGuffin(s) that assured South Korea’s rise to its pseudo-religious (and notably non-Christian) status as “esports Mecca” (Choe, 2021). It should be noted, then, that while scholarly pc bang studies have mapped the pc bang’s importance to Korean social, cultural, technological, and economic histories, the work that is, frankly, more readily consumed by esports publics has largely rendered the pc bang as an essentially (but incorrectly) Korean technological innovation. The SC2VN’s aesthetic and setting choices reflect this mythos in GZ’s aesthetic design and use as narrative infrastructure. Mach’s journey undertakes a re-humanization of the Asian/Korean subject while also mapping a path to Western reclamation of esports futures by isolating and devouring the desirable aspects of Koreanness through the pc bang. Golden Zonefire is historically situated as a key site where these ambivalent threads come together and the West can finally isolate the apparatuses that produce Koreanness and take them, and the future, for itself.

Probes in Spaaaaace

Because visual novels operate broadly through point-and-click dialogue choices, setting designs like Golden Zonefire’s are the SC2VN’s narrative infrastructure and mediate the game’s drama. Following Murray’s (2017) assertion that in-game representations often reflect Orientalist knowledges and historical epistemes (p. 86), I argue that Golden Zonefire’s design presents a socio-culturally constructed knowledge of essentialized Koreanness. Its design and integration into the SC2VN’s story are a historical footprint of North American esports in 2015.

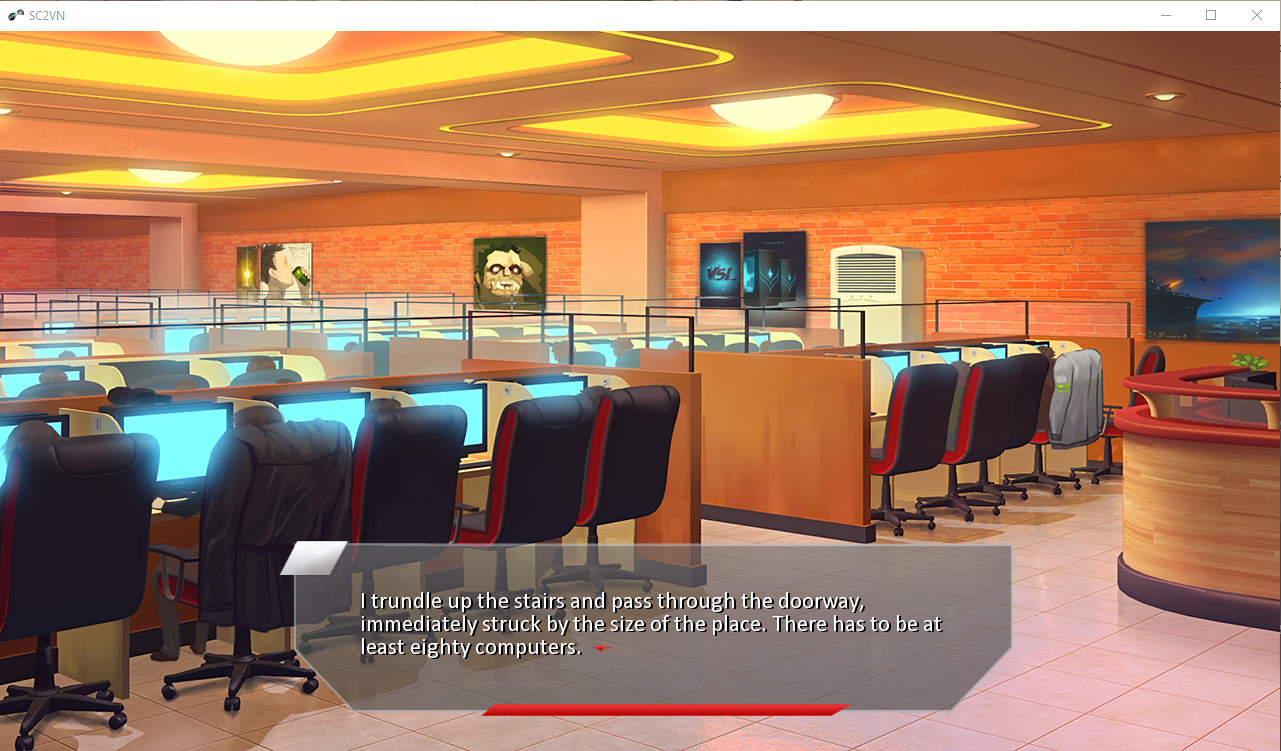

Golden Zonefire is designed as a place of light and warmth. Players first enter GZ as a place of bustling, well-lit social activity: giant, warm-toned overhead lights blaze from above; broad, wooden, multi-person desks hold four or five computers apiece with light blue screens shining; and red brick walls, adorned with ads and posters, wrap Mach and the other occupants in a glowing warmth. A large climate control unit is stacked against the far wall. The front desk has a small, leafy plant sticking out of the corner.

The pc bang’s welcoming warmth facilitated the drama by reflecting the setting’s importance to Mach’s subjectivity and social situation. This warmth foils other settings by drawing the player in and by facilitating the friendships that teach Mach how Korean esports works and how to internalize those best practices. In other settings where Mach explores their feelings of isolation and remembers how Korean characters mark Mach’s foreignness. Mach’s parents refuse to validate their career choice (Mach’s father notably says, “[They] have to make [their] own mistakes”), and Mach’s Western friends don’t understand Mach’s desire to be a StarCraft pro and judge them for it. Mach mainly reflects on these memories in their apartment.

Figure 2: The main room of Golden Zonefire. Screenshot by the author.

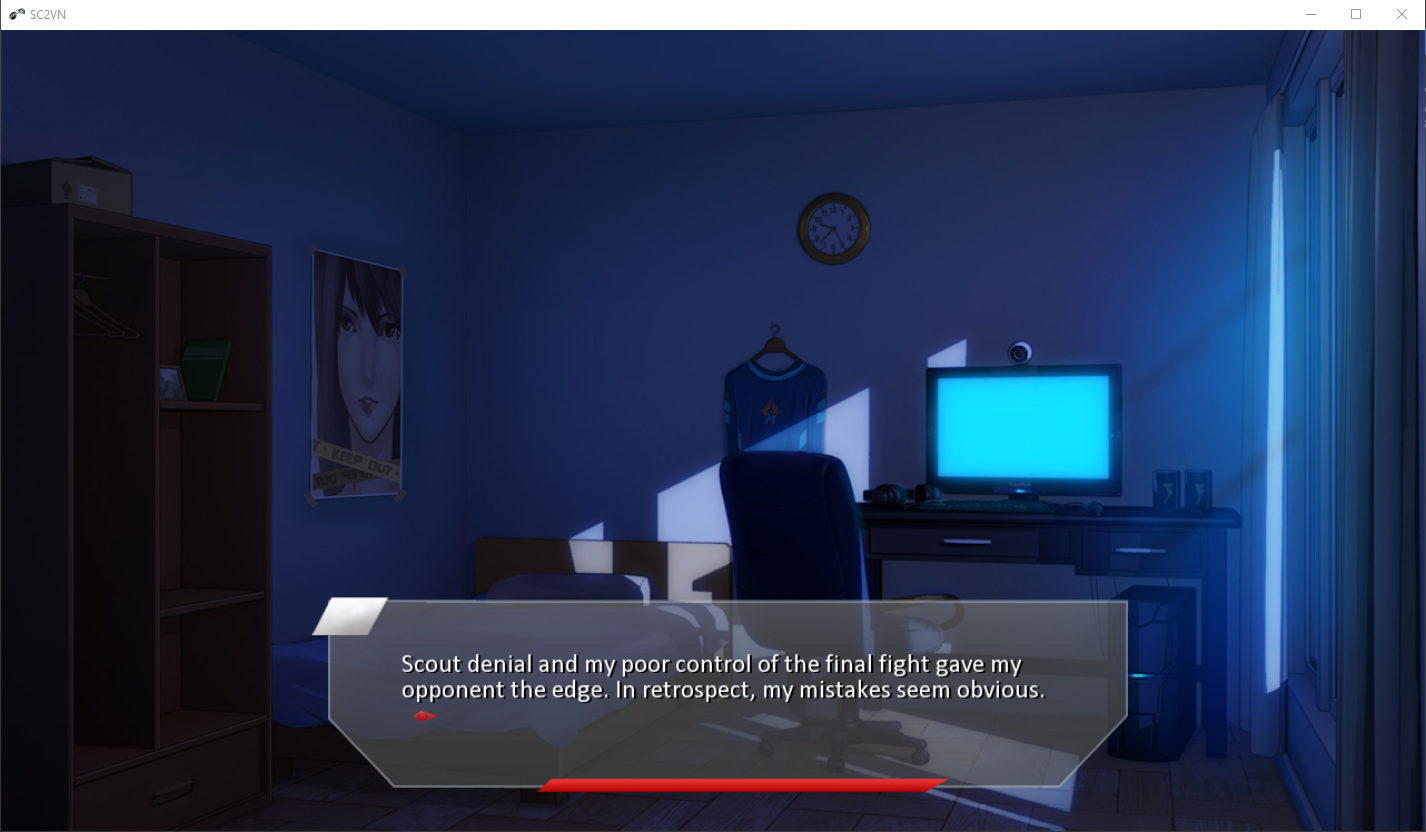

Mach’s apartment is awash in the cool-toned, blue light of their computer screen and the moonlight, the latter of which shines through a partially open curtain. The entire apartment space is one room, with a closet/shelf on the left, an idol poster in the shadows on the wall, and a low bed. Most of the room’s objects are also cool-toned—the blue jersey hanging on the wall, the computer screen, the black chair, and the black gaming computer with its blue power light. Even the desk is black. The floor, reflecting the lighting despite its wood textures, also holds a blueish hue. This is an infrastructure of loneliness, darkness, and despair.

Many of Mach’s darkest moments in the game happen in this apartment. It’s where Mach battles depression-like symptoms, feelings of isolation, overwhelmedness, and anxiety. At the game’s climactic scene, Mach suffers what seems to be a depressive episode and fails to show up to practice with their teammates. The team captain, Jett, shows up, slaps Mach in the face, and chews them out for abandoning their teammates. The cool-toned imagery is isolation. It’s loneliness.

Figure 3: Inside Mach’s cool-toned apartment. Screenshot by the author.

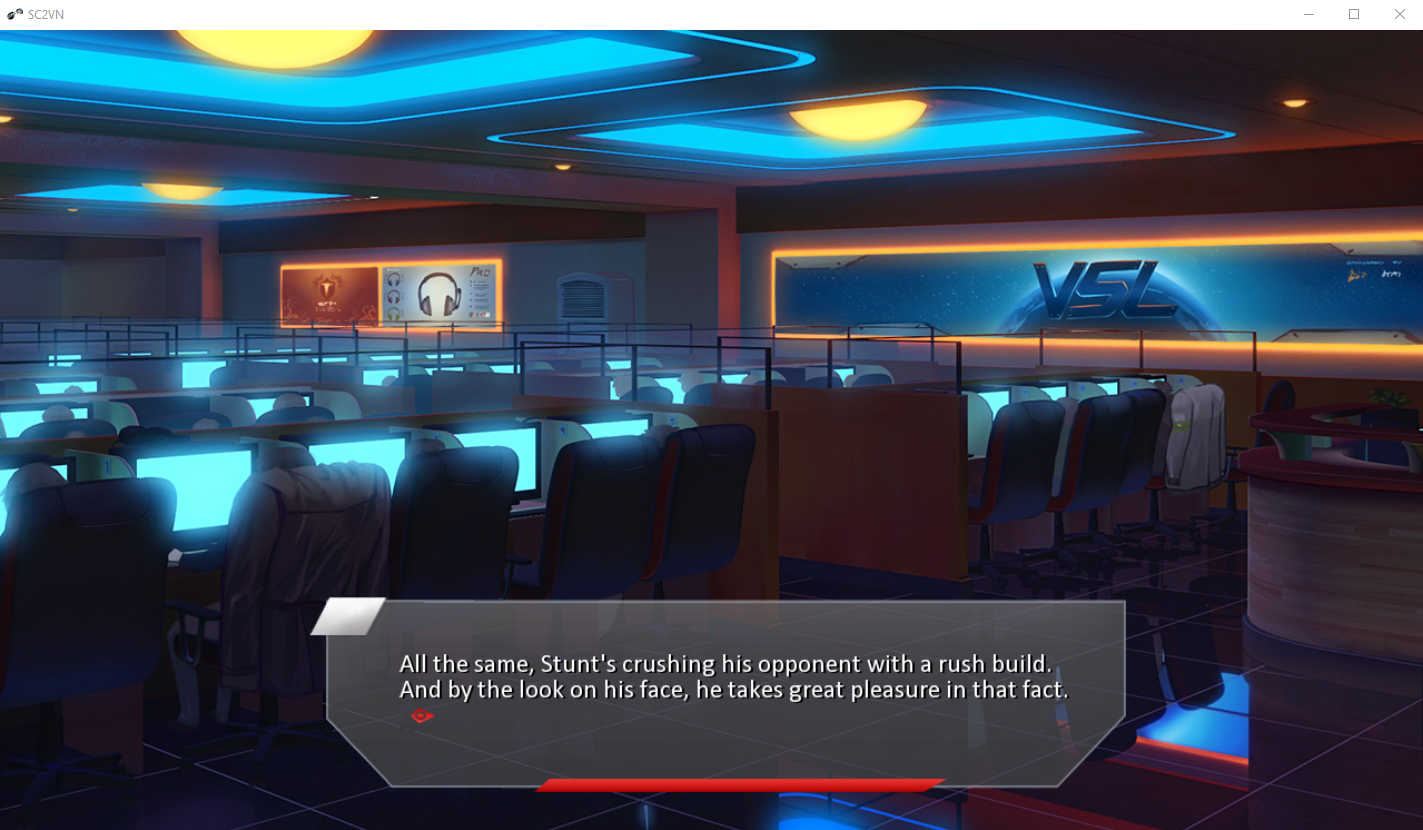

Beyond the apartment, though, Golden Zonefire also differs starkly from other pc bang, both in-game and out of it. Mach meets an eventual teammate in Stomping Grounds, a different pc bang. Unlike GZ, Stomping Grounds is dark, shadowy, and stained in the same cool, blue tones as the apartment. Mach compares it to a casino pumping extra oxygen to its inhabitants, implicating old tropes about Asianness and gambling addictions—reiterating the key high-tech Orientalist idea of selective appropriation of Asian subjectivity by rejecting this space. There is the Koreanness we want and the kind we don’t. This lays out Koreanness’s comparative tension, which affects Korean/Americans subjectivation in esports culture. The essentialized Koreanness in esports contexts is a specific, warm, social/bonded one, not this cold, dark place. Mach takes Stunt to GZ.

Scholarly descriptions of pc bang reveal GZ to be a trope by mapping out a less-polished, more comprehensive vision of Korean internet cafes. While GZ was designed with only two spaces—the computer area and a rest/vending machine area—many pc bang feature separate spaces for couples, smoking and non-smoking spaces, more diverse internet usage (email, chat, online dating), and shabby exteriors (Stewart & Choi, 2003, pp. 64, 67; Choi et al., 2009, pp. 135–136; Chee, 2012, pp. 39–42). Sometimes, displaced people use these spaces as cheap shelter (Chee, 2012, p. 102). While Mach describes a seamless gaming experience in GZ, scholars like Chee (2012) dealt with out-of-date software, login issues resulting from not having a Korean social security number, and gender expectations disrupting access to the Korean gaming experience (p. 40). In contrast to these depictions, Golden Zonefire promises a “noiseless” gaming experience where the assemblage of bodies, games, and infrastructures come together without impeding the speed and accuracy necessary for quality StarCraft II play (Taylor & Elam, 2018, p. 243). This noiselessness is one of SC2VN’s contributions to the West’s essentialized Koreanness through its design. Mach can focus on their esports dream without interruptions from hardware, software, hostile sociality, or bad practice partners in the West or at a lesser pc bang. Desirable Koreanness, through Golden Zonefire, is a raced, techno-utopian vision of noiselessness in esports labor.

Figure 4: Golden Zonefire’s warmth is different from Stomphing Grounds’ cold palette. Screenshot by the author.

The SC2VN enables an English-speaking audience to visit this quintessentially Korean site within the Western esports imagination as a form of tourism. Both identity and offline tourisms give “users a false notion of cultural and racial understanding based on an episodic, highly mediated experience of travel” (Nakamura, 2008, p. 1675). Accordingly, this guided tour through Seoul and Korean esports leans on recognizable tropes of Korea and Korean esports to make its setting sensible to an audience that likely has not experienced such spaces directly. Essentialized Koreanness mediates the game’s narrative movements, travel, and interactions controlled by the game’s writing, the visual novel format, and the settings that compose the narrative’s infrastructure. This travel could grant a false sense of understanding Korea through this American tourist experience, and essentialized Koreanness in North American esports is revised in that epistemic process. The SC2VN constructs the pc bang as an idiomatic representation of Asiatic Koreanness to make its settings recognizably Korean-ish for its primarily Western audience. GZ’s idiomatic code is built on the pc bang’s mythology as the place where esports Koreanness is born.

Figure 5: Early scene where Mach appraises the player of their situation. Screenshot by the author.

Over the course of the game, Golden Zonefire wears many hats, but it is most idiomatically a womb where essentialized Koreanness is (re)produced. Mach doesn’t even have basic etiquette down at the beginning of the story and requests a match with another patron nearby. Jett scolds them, telling Mach that this is not something you do, and Mach’s growth into Koreanness begins. Mach’s Westernness and non-Koreanness is established most concretely through incidents like this at GZ and through difficulties turning StarCraft play into StarCraft work, marking both behaviors and in-game skill as essentially Korean. It presents the Western audience with xenophobia and eating the Other as tourist attractions, while also Othering these Korean characters for their intolerance. Several characters mark Mach’s foreignness as essentially ill-suited to professional esports. White Western bodies, then, are allowed to tour the experience of being essentialized and view the techno-Orientalist future-present, but through the mediation of a harmless visual novel they choose to engage with. It is a masochistic amusement with the experience of “safe” xenophobia and techno-Orientalism characterized by video games and anime hair instead of, say, caged children on the U.S.-Mexico border.

Additionally, Mach’s recruitment to a pro team was primarily a tokenistic engagement with foreign fans than with Mach’s worth as an SC 2 player, thus equating StarCraft skill with Koreanness. From the outset, the skilled SC 2 players are Korean and Mach is not. This engenders Koreanness as a desirable thing to be acquired. The grounds for becoming accepted are initially set at being South Korean, so all Mach can do is become as Korean as possible. Further, this does not deviate from Mach’s initial episteme. Mach came to Korea because they want to get good at StarCraft, and Korea is most skilled region (Team Eleven Eleven, 2015). Mach is here because Korea is desirable, and in making it clear that Mach is not good enough to go pro on their own, the SC2VN makes Koreanness even more desirable for the Western gaze—a connection crystallized in the surge in Korean player contracts and practice adoptions in late 2010s esports (Voorhees & Howard, 2021).

As hooks (1992) put it, it is the possibility of transgressing against the norm—going pro in the West and getting smacked down by Korean opponents—that is desirable deviance for the Western foreigner (p. 369). It becomes a resistance to Western understandings of essentialism by essentializing Others who can provide what the Western subject lacks. To partake of Koreanness by immersing oneself in it, truly diving into it, and extracting the pearls needed from it provides the Western esports subject with a means to stop losing an international squash match. Koreanness can be identified, isolated, and devoured to reset Whiteness as the default orientation.

The ways GZ facilitates emergent Korean esports apparatuses is key to this rhetoric and the essentialized Koreanness it produces. Relations of practice arena, social space, team-building, professional networking, and entrepreneurial investment building all happen there, and these relational apparatuses produce essentially Korean esports subjects. This is important because GZ is a site of revelation where the high-tech Orientalism of the Western esports imagination is made plain. GZ’s warmth reflects White hope that lives in the pc bang. Not unlike Preciado’s (2019) illustration of Playboy and indoor space as gendered, biopolitical womb, the pc bang is imagined as a racial-biopolitical womb, where Mach’s White orientation incubates within Korean space to deviate from techno-Orientalist White futures. Learning Korean esports production processes means knowing and understanding it in a way Mach (and audiences) had not previously, producing epistemic revisions to essentialized Koreanness in the service of White supremacy. To inhabit GZ is not only to transgress upon spaces of Koreanness and become a productively deviant Western subject; it is also a means of learning how the best mousetraps are built, that they might be made obsolete.

With this knowledge in hand, Mach escapes the womb in rebirth, joining their new teammates in a Team House. The high-tech Orientalist pc bang fantasy, thus far synonymous with Korean esports, has established the Otherness of Korean esports players, cracked open their subjectivities to show the White, Western player what makes them tick, and now, finally, held the promise of escape from its own confines and the hostile, techno-Orientalist future inaccessible Koreanness represents in esports discourses. When the game concludes and Mach moves into the house with their teammates, this signals Mach’s membership as one of the Koreans. Mach learned how to practice 14 hours a day, how to navigate Korean esports sociality, how to work toward their goals intentionally, and how to be a member of a society that accepts Mach’s aspirations. The Koreans are the future of modernity in this narrative, while Mach is a possible path forward for Whiteness. Their friends and parents are rejected, their normative Whiteness old and un-modern as they are reborn as a raceless deviant defining a new White future. Could a Korean/American do the same just as easily?

In producing this vision of future Whiteness that appropriates gaming and esports Koreanness, the SC2VN co-produces a vision of Koreanness to appropriate. Korean diaspora, like Korean/Americans, live with this epistemic revision. The pc bang, and by proxy Korea, are a warm, nurturing womb and a birth canal for a new Whiteness, but this vision also produces a colonized knowledge of essentialized Koreanness that expresses White desires. Therefore, the Whiteness most at play in the SC2VN is not merely the high-tech Orientalist datafication of Koreanness in the service of default Whiteness, but the (re-)production of an essentialized Koreanness imposed upon individual Korean/American subjectivities.

Conclusion: A Bang with a View

The SC2VN offered a counter-narrative to Korean roboticism in esports, but it also reflected a techno-Orientalist Western essentialism toward a Korean esports Elsewhere. The visual novel’s central conflict is Mach’s Westernerness in a foreign land, and Golden Zonefire becomes the space most synonymous with that setting through its role as Korean womb. The pc bang’s aesthetic design as a place of beckoning hope, centrality to the story, and roots in Western esports mythologies surrounding Korean dominance presents players with an Asiatic Korea—a Korean-ish essentialized Koreanness that makes GZ a visual idiom for South Korean all of esports. As a womb, GZ incubates its Western esports subject in a fantasy of South Korean esports success, while eventually re-birthing Mach as un-foreign through their appropriation of a techno-Orientalist essentialized Koreanness in a race-nation-media articulation. Mach maps the proper, Korean way to work gaming technologies and shows how to seize it. They are also the product of and avatar for a constituted audience of worried White esports fans who travel with Mach to lands unknown.

GZ’s aesthetic design and infrastructural role both produces a recognizable Korean esports apparatus that allows Western subjectivities to define themselves in relation to it and shifts the orientation of the White subject to a position that can more easily reach what it desires (reclamation of imperial power in esports contexts). This means that while Mach and the assumed White, Western player is there, GZ is simultaneously a space of differentiation, dissection, and dissent from a narrative of White, Western obsolescence in esports. The pc bang is a window to Korean difference and a womb that produces essentialized Korean esports subjects, even in the case of the Western interloper. The White, Western fish-out-of-water can become Korean here. The SC2VN may have intervened by making the subjects of esports discourses in the West more human through its characters, but GZ also reveals the game’s failure to escape its own cultural-historical context. In a twisted way, it’s ultimately a game about trying to become Korean enough, as an outsider, to make it in an esports industry where being Korean seems to coincide with success.

Looking westward, the game’s Orientalist narrative lacks consideration for members of Korean diaspora, many of whom already struggle with “Korean enough” within and beyond esports. The tension between essentialized Koreanness and individual Korean/American subjectivation feels painfully trivialized by SC2VN. It reminded me of a piece by Jung (2018), when he talked experiences of ethnic return to Korea after living in the U.S. most of his life. Jung argued that living in Seoul for three years revealed the ambiguity of his subjectivity: there, he was a foreigner who looked native, and in the States, he was the subject of anti-Asian racism. In both cases, Jung describes his individual Koreanness in relation to essentialized Koreannesses around him, and this alienated self-coalesces at that tension point. Being “not Korean enough” or “too Korean” is already a lived experience for many people.

When I first played the SC2VN, I played mostly as a white man and esports fan because my multiracial Koreanness served me best as a party trick to impress new acquaintances. From that orientation, I finished the game flush with hope and happiness, assured that the West would figure esports out eventually. The second time I played, willing to identify (messily) as a mixed-race Korean/American, I felt little warmth in that White protagonist’s journey. If Golden Zonefire made Korea knowable to White, Western subjects, it no longer makes it knowable to me in a way I can accept. Instead, it reiterates in this imagined Seoul what Jung describes as, “…a city filled with expats who do not necessarily love the city, but rather, love what it can do for them. They love who they can become” (Jung, 2018).

This entitlement to possibility flies in the face of Korean/American experiences. Mach can travel to South Korea to be a pro gamer without experiencing the racism toward Black or Brown bodies critiqued by recent Korean media like Itaewon Class (2020) or Squid Game (2021). The historical inheritance of Whiteness that allows expats to become something they love in Seoul maps Whiteness’s global nature, and differs starkly from Jung’s experiences in Korea trying to understand himself. Korean/American subjectivation and Koreanness are both trivialized in the service of White supremacy, where an Asian/American point of tension becomes a White tourist attraction where the struggle between being “too Korean” in North America and “not Korean enough” abroad platforms a liberal-humanist techno-fantasy through sensible aesthetics and narrative design. If Mach were racialized as Asian or Korean, they would draw the scrutiny of essentialized Koreanness applied to Jung and others, like Hines Ward or Daniel Henney (Ahn, 2014, pp. 399–400; Ahn, 2018, p. 104).

Asking what Seoul’s pc bang can do for Mach and Whiteness renders the humanized Korean characters trappings of a broader socio-cultural reproduction in Western esports: what about Koreanness holds the seeds of its own downfall? For members of the Korean diaspora, what work—indeed, what damage—does this sort of game design do? What do we see when we witness the game’s recapture by the origins of its own intervention? While both halves of my gene pool are in this game, my own subjectivation finds little purchase in a tale that reproduces my high-school survival strategies as the solution to Western esports’ Korean problem. Instead, I found, like Jung, alienation, caught in but ignored by the tension between North American esports’ gaze East and my own sense of self.

Endnotes

1. It is necessary to point out that while the pc bang is situated in ways very specific to South Korean culture, space, and sociality, among other histories, the institution of internet cafes with specific gaming focused rooms is prevalent in other places, especially in Asia.

2. It should be noted that Shields’ reputation is decidedly mixed, and that many his opinions have remediated harmful rhetorics from hegemonic gaming demographics. It is my hope that my citing some of his work does not present any kind of support for the way he uses his platform.

Author biography

Matthew Jungsuk Howard is a PhD Student in Communication, Rhetoric, & Digital Media at North Carolina State University. He studies the movements and constructions of Koreanness in digital media contexts such as esports, music, food, and television, and he’s most interested in cultural logics of nationality, racialization, diaspora, and transnationalism, particularly through postcolonial lenses. His current driving questions ask how different kinds of platformization and globalized digital cultural production disrupt, perpetuate, and/or resist the dynamics of settler colonialism, especially as experienced by people navigating the fluid process of identity construction.

Trained as a cultural historian with a background in world history, Matt is concerned with the ways power works through technological and socio-cultural conventions governing how we have spent our free time, as well as how those interactions affect the ways people know the world and themselves within it. Some of his hot-button topics include Asiatics, racial passing & hybridities, feminisms & masculinities, historical knowledge constructions, and subjectivation in global contexts.

References

Ahmed, S. (2007). A phenomenology of whiteness. Feminist Theory, 8(2), pp. 149–168.

Ahn, J. H. (2014). Rearticulating Black mixed-race in the era of globalization: Hines Ward and the struggle for Koreanness in contemporary South Korean media. Cultural Studies, 28(3), pp. 391–417.

Ahn, J. H. (2018). Mixed-race politics and neoliberal multiculturalism in South Korean media. Palgrave Macmillan.

Bae, K. Y. (2021). ‘Too many Koreans’: Esports biopower and South Korean gaming infrastructure. In M. Lee & P. Chung (Eds.), Media technologies for work and play in East Asia: Critical perspectives on Japan and the two Koreas (pp. 205–228). Bristol University Press.

Blizzard Entertainment. (1998). StarCraft: Brood War.

Blizzard Entertainment. (2010). StarCraft II: Wings of Liberty.

Blizzard Esports (2014, September 4). Upcoming Changes to WCS 2015. Battle.net. https://web.archive.org/web/20160306082129/http://wcs.battle.net/sc2/en/articles/upcoming-changes-to-wcs-2015. Accessed through Wayback Machine.

Boluk, S. & Lemieux, P. (2017). Metagaming: Playing, competing, spectating, cheating, trading, making, and breaking videogames. University of Minnesota Press.

Bury, J. (2017, June 6). Deficio: ‘The problem with [saying] the gap is closing is that there are two different gaps. The one to Korea and the one to SKT’. TheScore eSports. https://www.thescoreesports.com/lol/news/14362-deficio-the-problem-with-saying-the-gap-is-closing-is-that-there-are-two-different-gaps-the-one-to-korea-and-the-one-to-skt.

Carroll, H. (2011). Affirmative reaction: New formations of white masculinity. Duke University Press.

Chee, F. (2006). The games we play online and offline: Making Wang-tta in Korea. Popular Communication, 4(3), pp. 225–239.

Chee, F. M. (2012). Online games as a medium of cultural communication: An ethnographic study of socio-technical transformation [Doctoral dissertation, Simon Fraser University].

Choe, S. H. (2021, June 19). Inside the ‘Deadly Serious’ world of e-sports in South Korea. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/19/world/asia/south-korea-esports.html.

Choe, S. & Kim, S. Y. (2015). Chapter 8: Never stop playing: StarCraft and Asian gamer death. In D. S. Roh, B. Huang, & G. A. Niu (Eds.), Techno-Orientalism: Imagining Asia in speculative fiction, history, and media (pp. 113–124). Rutgers University Press.

Choi, J. H., Foth, M., & Hearn, G. (2009). Site-specific mobility and connection in Korea: Bangs (rooms) between public and private spaces. Technology in Society, 31, pp. 133–138.

Chuh, K. (2003). Introduction: On Asian Americanist Critique. In Imagine otherwise: On Asian Americanist critique (pp. 1–29). Duke University Press.

Chuh, K. (2019). The difference aesthetics makes: On the humanities “after man”. Duke University Press.

Chun, W. H. K. (2008). Orienting the Future. In Control and freedom (pp. 171–245). The MIT Press.

Chun, W. H. K. (2011). Race and/as technology; or, how to do things to race. In L. Nakamura & P. A. Chow-White (Eds.), Race after the internet (pp. 38–60). Routledge.

Day, I. (2016). Alien capital: Asian racialization and the logic of settler colonial capitalism. Durham, NC. Duke University Press.

Deesing, J. (2014, December 12). The South Korean Exodus to China. RedBull Esports. https://www.redbull.com/us-en/the-south-korean-exodus-to-china.

Discover Digest. (2014, March 14). Korean PC Bang [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/L2sAPfqgvXw.

Dyer-Witherford, N. & De Peuter, G. (2009). Games of empire: Global capitalism and video games. University of Minnesota Press.

Erzberger, T. (2016, October 14). Erzberger: The gap is not closing in League of Legends. ESPN. https://www.espn.com/esports/story/_/id/17794800/gap-not-closing-league-legends.

eSports Earnings. (2015, September 23). Top countries for StarCraft: Brood War—e-Sports player rankings. https://www.esportsearnings.com/games/152-starcraft-brood-war/countries. Accessed through Internet Archive.

eSports Earnings. (2015, September 18). Top countries for StarCraft II—e-Sports player rankings. https://www.esportsearnings.com/games/151-starcraft-ii/countries. Accessed through Internet Archive.

Fickle, T. (2018). The race card: From gaming technologies to model minorities. New York University Press.

Fickle, T. (2021). Made in China: Gold farming as alternative history of esports. ROMChip 3(1).

Foucault, M. (1969). The archaeology of knowledge. Routledge Classics.

Harper, T. (2013). “Asian Hands” and Women’s Invitationals. In The culture of digital fighting games: Performance and practice (pp. 108–133). Routledge.

hooks, bell. (1992). Eating the other: Desire and resistance. In Black looks: Race and representation (pp. 21–32). South End Press.

Howard, M. J. (2018). Esport: Professional League of Legends as cultural history (https://uh-ir.tdl.org/handle/10657/3298). [Master’s thesis]. University of Houston.

Huckabee, T. (2016). SC2VN – The eSports Visual Novel. Kickstarter. https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/vogue/sc2vn-the-esports-visual-novel/posts.

Huhh, J. (2008). Culture and business of PC bangs in Korea. Games and Culture, 3(1), pp. 26–37.

Jin, D. Y. (2010). Korea’s online gaming empire. The MIT Press.

Jin, D. Y. (2020). Historiography of Korean esports: Perspectives on spectatorship. International Journal of Communication, 14, pp. 3727–3745.

J. K. (2020, March 26). Brief History of Esports in Korea & Why Is It So Famous There. Korea Game Desk. https://www.koreagamedesk.com/brief-history-of-esports-in-korea-why-is-it-so-famous-there/.

Jung, E. A. (2018, March 26). I Thought Going to Korea Would Help Me Find Home. BuzzFeed News. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/ealexjung/korean-american-asian-american.

[jreece]. (2015, August 27). Re-examining the Samsung Exodus. Dot Esports. https://dotesports.com/league-of-legends/news/reexamining-the-samsung-exodus-6053.

Khaw, C. (2015, October 11). SC2VN visual novel review: An impassioned homage to StarCraft II. ArsTechnica. https://arstechnica.com/gaming/2015/10/sc2vn-visual-novel-review-an-impassioned-homage-to-starcraft-ii/.

Kolev, R. (2013, October 24). On WCS region locking and why it may be a bad thing. Gosu Gamers. https://www.gosugamers.net/starcraft2/features/37554-on-wcs-region-locking-and-why-it-may-be-a-bad-thing?comment=575578.

Leesman, J. (2016, September 29). The gap is closing. TwitLonger. http://www.twitlonger.com/show/n_1sp5c6e.

Li, R. (2016). Good luck, have fun: The rise of eSports. Simon & Schuster.

LoL Esports. (2018, October 4). A Korean Pro’s Journey – The PC Bang feat. Madlife | Worlds 2018 [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/2yfwNELSzqY.

Maiberg, E. (2015, September 18). This Visual Novel is the Best Way to Understand ‘StarCraft’. Motherboard: Tech by Vice. https://www.vice.com/en/article/4x3jew/this-visual-novel-is-the-best-way-to-understand-starcraft.

Miller, H. (2020, September 14). Can gaming centers become the US version of PC Bangs? Dot Esports. https://dotesports.com/business/news/can-gaming-centers-become-the-us-version-of-pc-bangs.

Morley, D. & Robins, K. (1995). Spaces of identity: Global media, electronic landscapes, and cultural boundaries. Routledge.

Mozur, P. (2014, October 19). For South Korea, E-Sports Is National Pastime. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/20/technology/league-of-legends-south-korea-epicenter-esports.html?_r=0.

Murray, S. (2017). The Poetics of Form and the Politics of Identity in Assassin’s Creed III: Liberation. Kinephanos, Gender Issues in Video Games, 77–102.

Nakamura, L. (2008). Cyberrace. PMLA, 123(5), pp. 1673–1682.

Patterson, C. B. (2020). Introduction: Touching Empire, Playing Theory. In Open world empire (pp. 1–35). New York University Press.

Preciado, P. B. (2019). Pornotopia. Zone Books.

Riot Games. (2015, January 8). League of Legends Championship Series 2015 Season Official Rules. Accessed through Gamepedia. https://lol.gamepedia.com/File:LCS_2015_Rulebook.pdf.

Roh, D. S., Huang, B., & Niu, G. A. (2015). Technologizing Orientalism: An Introduction . In D. S. Roh, B. Huang, & G. A. Niu (Eds.), Techno-Orientalism: Imagining Asia in speculative fiction, history, and media (pp. 1-19). Rutgers University Press.

Said, E. W. (1979). Orientalism (Vintage Books Edition). Vintage Books.

Seif El-Nasr, M., Al-Saati, M., Niedenthal, S., & Milam, D. (2008). Assassin’s Creed: A Multi-Cultural Read. Loading, 3(2).

Shields, D. (2014, October 18). Western pro-gamers shouldn’t want to be like Koreans. Dot Esports. https://dotesports.com/league-of-legends/news/western-progamers-shouldnt-want-to-be-like-koreans-5759.

Shields, D. (2015, January 15). Thorin’s Thoughts – Koreans Would Dominate any Esports Game [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/00LjRaBtxcs.

Showbox/Mediaplex, Zium Content. (2020). Itaewon. [Netflix]

Siren Pictures Inc. (2021). Squid Game. [Netflix]

Stewart, K. & Choi, H. P. (2003). PC-Bang (room) culture: A study of Korean college students’ private and public use of computers and the internet. Trends in Communication, 11(1), pp. 63–79.

Stickney, A. (2015, September 16). BlizzCrafts: Talking SC2VN with Timothy Young and TJ Huckabee. Blizzard Watch. https://blizzardwatch.com/2015/09/16/blizzcrafts-talking-sc2vn-timothy-young-tj-huckabee/.

Taylor, N. & Elam, J. (2018). ‘People are robots, too’: Expert gaming as autoplay. Journal of Gaming & Virtual Worlds, 10(3), pp. 243–260.

Team Coco. (2016, April 13). Conan Checks Out A PC Bang | CONAN on TBS [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/TPXWtozVNzM.

Team Eleven Eleven (2015). SC2VN: The Esports Visual Novel [Digital Game].

theScore esports. (2018a, November 18). What is a PC Bang? The Story Behind the East’s Gaming Cafes [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/_CkBYvEtxyU.

theScore esports. (2018b, November 29). The Great Korean Exodus: How huge Chinese contracts gave us LoL’s craziest offseasson ever [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/olpBaV6Eavo.

Today on the Korean Server. (2016, June 28). Inside a Korean PC Bang and why is Overwatch dominating [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/cI-tyGaMSLo.

Ubisoft. (2012). Assassin’s Creed III: Liberation.

Ueno, T. (2002). Japanimation and Techno-Orientalism. In B. Grenville (Ed.), The uncanny: Experiments in cyborg culture (pp. 223–236). Arsenal Pulp Press.

Vogue kun. (2013, May 1). Starcraft 2: The Dating Simulator [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/a8COOrPHM-Q.

Voorhees, G. & Howard, M. J. (2021). High-tech Orientalism in Play: Performing South Koreanness in Esports [Manuscript submitted for publication].

Wei, W. (2015, October 18). What it’s like inside a ‘PC bang’ in South Korea [Video]. Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/south-korea-gaming-pc-bang-2015-10.

Wiley, S. B. C. (2004). Rethinking nationality in the context of globalization. Communication Theory, 14(1), pp. 78–96.

Wiley, S. B. C., Sutko, D. M., & Moreno Becerra, T. (2013). Assembling social space. The Communication Review, 13(4), pp. 340–372.

Zhu, L. (2018). Masculinity’s new battle arena in international e-sports: The games begin. In N. Taylor & G. Voorhees (Eds.), Masculinities in play (pp. 229–248). Palgrave Macmillan.