by Amanda Lange

Published January 2014

Download full pdf of article here.

Abstract

Some data available from games with moral decision systems show that gamers are generally unwilling to play as evil characters. In a study, over 1000 gamers were surveyed to see how the average player interacts with a game system that allows the player to choose a “good” or “evil” path through a game story. The finding was that the average gamer prefers to be good or heroic in such games. Gamers are most interested in exploring a character whose moral choices closely match to their own. However, those players that experience a game for the second time are then more likely to choose evil. The article includes an exploration of which actions gamers felt particularly evil, and what kind of choices turn out to be more difficult for them.

My prediction is: all you guys, you’re just gonna be nice. Sickeningly, sycophantically nice to each other. And it makes me sick, because you know, in a game like Fable, we spent hours; we spent months, months and years crafting the evil side of Fable, and only ten percent of people actually did the evil side. Come on. You’re supposed to be gamers. (Peter Molyneux, 2013)

I am the ten percent.

And I find myself frustrated in conversations with gamers with similar tastes to mine in their absence of moral imagination. I know I am not my avatar in the game, so I like to experiment. Sometimes it’s entertaining to me to see the results of a choice I would never make in reality. Sometimes it’s just plain fun to be the bad guy. But it seemed to me that many other gamers I have spoken with have no interest in transgressing moral boundaries in story-based gaming. Their aversion to this, though I find it boring, poses some interesting questions for game designers.

A binary moral choice system has achieved a great deal of popularity in game design over the past decade. In the game Fable (Big Blue Box, 2004), as described above, there are certain segments based on player choice. The player may choose to do an explicitly labeled evil act, decreasing the in-game karma score of the player’s avatar, or a good act, which causes the character to gain in-game karma and become more heroic. This kind of system has appeared in different forms in game franchises, such as Mass Effect, inFamous, BioShock, Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic, and Fallout. Other games, such as The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim (Bethesda Game Studios, 2011) or Dragon Age, contained moral-decision elements that are labeled by character traits or present branching narrative without an overt karma score. Still other games, such as Spec Ops: the Line (Yager Development, 2012), contained hidden moral decisions that ask the player to commit an act in the heat of a moment. The avatar may then be considered more good, or more evil, based on the game’s judgment.

Though all games seem to define good and evil slightly differently, most games are explicit about indicating which choice was made after it was made or during that choice’s execution. A few judgments are common. Games generally consider non-violent solutions to be good solutions when they are available, and consider overtly violent solutions to be evil regardless of the context or amount of violence elsewhere in the game. Creating wanton property damage or subjugating people is evil, advocating freedom is seen as generally good, and the promotion of social equality and justice are considered good. Betrayal of former friends is considered an evil act, as is ignoring the pleas of an innocent when something can be done to help them. Games seem to generally consider actions done with a pure profit motive to be evil, but they may reward actions done altruistically in such a way that, while the roleplayed character has no profit motive, the player still makes an in-game profit on the good act. In these situations, the player is rewarded for an avatar’s supposedly selfless behavior. The Project Horseshoe Think Tank referred to these choice moments as “ethical dilemmas” and did a broader set of case studies about how they are typically presented in games, including examining games not frequently considered as moral choice games and tracking how those games presented and “scored” such dilemmas (Schreiber et al., 2009).

The Status Quo

We already have some statistics for how players engage with these elements, through data-mining of the games directly. Molyneux (2013) claimed ten percent played evil in Fable. The Mass Effect 3 (BioWare, 2012) team reported a third of players chose Renegade (evil-flavored) versus two-thirds Paragon (good-flavored) (Totilo, 2013). The recent zombie adventure series, The Walking Dead (Telltale Games, 2012), not only tracked how many people made which decision in which branch, but also displayed this to players in a series of video trailers (Fogel, 2012).

However, there are a few things that I felt current data mining couldn’t adequately express. For example, a common sentiment among gamers in a game that can be played as good or evil is to play good in the first playthrough. Evil is held for a second, lower-priority playthrough after they’ve played the game “correctly.” Having total statistics does not take this propensity into account.

I was also interested in seeing how moral choices correlated with the player’s and avatar’s gender. Based on earlier research from Heidi McDonald (2013) about identity tourism in games, I already suspected that male gamers would be more likely than female gamers to choose an avatar different from their own gender. Her research also showed that even though women were more likely to create an avatar that looked like them, they were not as likely to play out that avatar’s romantic choices the same way they felt they would in real life. I wondered if this could be applied to moral choices as well. My hypothesis based on available data was that only a minority of male gamers would choose the evil path in a moral-choice game. I also expected that there would be a correlation with a female avatar and the evil path, since many gamers also switch genders on a second playthrough. I wondered if there might also be a correlation between female players and evil: If women are more likely to choose a dangerous romance in a game, are they also more likely to make darker moral choices?

The Study

Over the past few months I’ve been conducting a survey of video gamers, asking them how they approach this type of choice in video games. Participants were recruited via Twitter, a Reddit community dedicated to video games, and a news post to a games and game-culture blog. A total of 1067 gamers responded to this survey. In the survey, I asked different questions depending on if the gamers reported they only played a game once, or if they liked to play the games more than once. The questionnaire also asked if players ever played avatars that had different gender identities than their own, and whether they played a different gender in their main or secondary playthroughs.

The questionnaire also had open-ended questions about how players interpreted moral choices in games. I was particularly curious about which acts players felt were too evil or made them feel guilty. Did players feel more rewarded playing heroically, or villainously?

These results should be interpreted cautiously. This was an exploratory study with a self-selected sample that may not be representative of the broader gaming environment. Probably the biggest flaw in this first study is that some people didn’t know what kind of games this survey was asking about, so they were unable to fully complete the survey. I purposely did not lead with the titles of any particular games, hoping those who responded would draw their own conclusions about which games included a moral choice system. In the future, I may focus on particular games or types of choices. Respondents were also 88 percent male, 10 percent female, with the remainder choosing “other” or electing not to respond. Based on this demographic it’s hard to draw too many conclusions about how women engage with these games. Sampling of data from spaces populated by a higher percent of female gamers may be necessary in a future study.

Factors such as game skill and familiarity may also influence the choices that players make in games. This study did not screen for players’ level of familiarity with games or ask about their favorite types of games. In a future study, gamers might be sorted based on their familiarity with games to see how this alters the data set.

Only 1 percent of responders claimed not to complete the games they played. This is obviously skewed, since statistically, most gamers do not complete games they play. Industry averages may be as low as ten percent for a very large game, such as Red Dead Redemption (Rockstar San Diego, 2010; Snow, 2011), or, for example, 42 percent of players of the aforementioned Mass Effect 3 (Phillips, 2012). Seeing this result on the survey may mean that a higher amount of people likely to respond to the survey are the sort of players that always finish games. Of these gamers surveyed, 60 percent claimed they play such a game more than once. That leaves 39 percent that claimed to only play the game once. Industry data-mining does not usually track or report replays, so it’s difficult to say how close this matches the average gamer.

The One-Timers

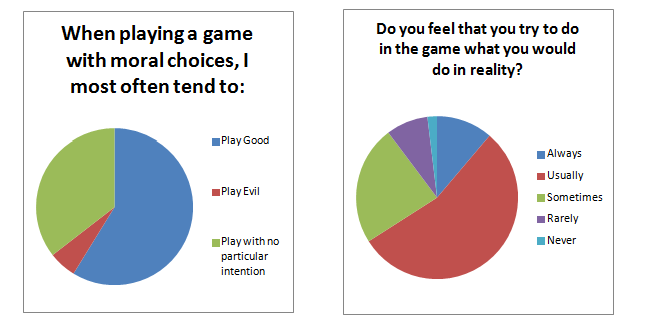

39 percent of survey participants claimed to typically play a game only once. Within that subset of players, 59 percent of participants played the game as a good character. 39 percent of those who played the game only once did not expressly play good or evil, but claimed to make decisions “on a choice by choice basis.” Five percent of participants played only evil. A majority of these participants (55 percent) said that they “usually” tried to really do in the game what they would actually do in real life. An additional 10 percent said they “always” did in the game what they would in real life, and 23 percent answered “sometimes.”

Choosing to do the right thing is the majority opinion among participants in their first playthrough. These gamers that responded are less interested in roleplaying a character who would do something other than what they would do in reality. They are rarely interested in playing as a role that has a different sense of morality than their own.

Double Dippers

Would gamers behave differently on their second playthrough compared to their first? Gamers had a number of reasons for starting a second playthrough. Many wanted to see new game content they had missed during the first play or to see the results of different choices. Gamers were also interested in “trying out new builds” in roleplaying games or earning Achievements/Trophies that they missed in their first playthrough.

Of the double-dipping gamers, 63 percent said that their first playthrough was the good one, 27 percent said they play on a choice-by-choice basis, and only 9 percent chose evil for their first playthrough.

49 percent of those who played the game more than once said that the evil playthrough corresponded to their second playthrough. 35 percent reported that the second playthrough was the neutral one, leaving only 16 percent of respondents who considered good to be the second option. Of those who reported that they played a game twice, a total of 80 percent of these respondents said they “always” or “usually” choose their real morality on their first time through the game.

In this answer, which allowed an open response, multiple gamers confirmed my suspicions exactly for how they engage with this content. One gamer summed up his motivations for a second playthrough: “So I can play the evil or neutral storylines. I always play through first following the good storyline.” Another respondent summed it up this way: “Play once as the lawful good hero, and once as the chaotic evil backstabber.”

Gender and Moral Choices

While women constituted a minority of replies to this survey, would they show any differences from men in moral playstyle? The female participants turned out to be similar to male participants in their moral choices. Of the women who played a game only once, 74 percent of them said they chose to play as the hero, with only 5 percent willing to admit they played as evil, corresponding to the overall data for all genders. 63 percent of the women who played games more than once chose to do a “first playthrough good” condition. 44 percent of these players followed up with an evil playthrough, and 38 percent neutral.

There was no strong correlation between the player identifying as female and amoral behavior. The relationship between avatar gender and amoral behavior was more ambiguous.

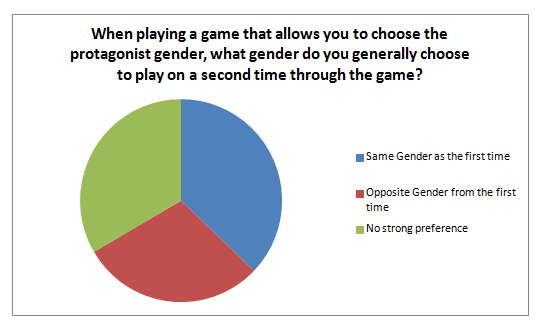

Only 9 percent of male respondents claimed to always swap genders (on a single playthrough). 59 percent said they typically played male with the remainder having no strong preference. When male gamers were asked if they swapped genders during a second playthrough (in games where this was an option) the results were mixed. 29 percent of male respondents said that they tended to swap genders the second time, 37 percent played the same both times, and 33 percent had no strong preference.

A total of 569 men, more than half the male respondents, claimed to play games more than once. A total of 63 of these men claimed to prefer to start with a male gender, then play female the second time. 65 percent of the gender-swapping men (a total of 41 responses) also played the game as evil during the female playthrough. Men who did not swap genders, on the other hand (a total of 166 respondents), were also less inclined to choose evil in the second playthrough and tended to choose “neutral” more often, though evil was still predominant (here, 44 percent in the evil condition, with 36 percent having chosen neutral).

There were not enough female participants in the study to draw a meaningful conclusion about women who play differently gendered avatars. However, of the five women who both claimed to play games twice, and swap genders the second time, three of them had the “first playthrough good, second playthrough evil” condition.

A further study on how avatar appearance and gender might affect moral transgression may be useful. Is it easier for a player to be evil when the avatar is an opposite gender?

What Counts as Evil?

Can video games make people morally uncomfortable? 43 percent of participants said they had encountered an act in a game that was vile enough that they refused to commit it. In some games, this would mean ending the playthrough.

Participants described their experiences using an open-ended response form. Many refused to harvest Little Sisters in BioShock (Irrational Games, 2007 – 2009), as killing a child was too evil to enact. Killing the “good dragon” Paarthurnax in Skyrim is very uncommon, despite the game story encouraging it. Many gamers refused to set off a nuclear weapon in the game Fallout 3 (Bethesda Game Studios, 2008). In some cases, gamers cited acts that were not moral choices, but necessary for the game to proceed. Several gamers cited the torture sequence in the recent Grand Theft Auto V (Rockstar North, 2013) as going too far for them, and many others reported extreme discomfort in using white phosphorus on civilians in the game Spec Ops: the Line or gunning down civilians in the famous Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2 (Infinity Ward, 2009) “No Russian” sequence. “I just didn’t shoot anyone,” said one gamer.

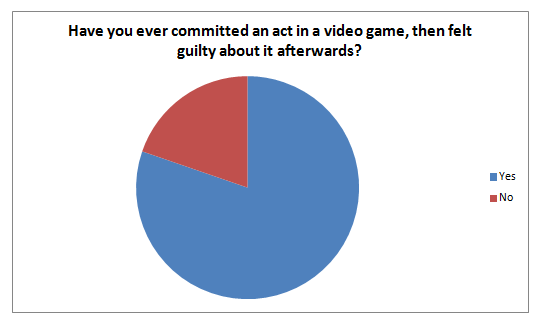

Moral objections that cause a termination of play seem to be a minority opinion among participants. 56 percent of responders said they never had a situation where they refused to commit an act in a game. Many participants were adamant that evil acts remain in games. They relish the opportunity to do bad. “It’s a game… not reality. The decision I take [sic] in the game have no impact on my life,” said one such response. 31 percent of respondents claimed to never have felt any guilt about an act they committed in a video game.

Crime and Punishment

Do gamers think it is fair for villainous actions to be rewarded? 90 percent of gamers said that this was fair. It seems that gamers are okay with evil being rewarded, even if they don’t often deliberately choose it. It also seems gamers generally have a high tolerance for feeling guilt or feel very little guilt.

At the same time, rewarding evil in a game environment may not necessarily be wrong, but punishing evil was generally perceived to be fair. Games that punish evil characters with prison, fines, or other downsides are generally doing the right thing by many gamers. In an open response about punishment, gamers replied with sentiments such as “To punish the player for doing evil things is the purpose of a moral system” and “I don’t think it’s unfair to punish you for an evil decision. Our entire society is built on that principle.” Another response said: “if it’s evil, you get what you deserve.”

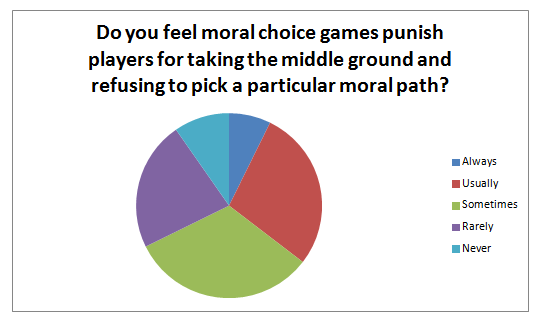

Most gamers seemed to feel that the good path for players was also the most rewarding path, with games only “sometimes” or “rarely” punishing players for making good choices. By comparison, the evil path more frequently was considered punishing, with the majority saying it was “sometimes” punished, but 23 percent believing it was “usually” punished.

Players sometimes complain about feeling forced to do evil when they do not want to, especially if they feel tricked. A few games that had extended negative responses:

In Skyrim:

You become a member of the thieves guild before you know it. You may not think that stealing is an inherently bad thing, depending on who you’re stealing from and in what circumstances. But these guys are an entire guild dedicated to stealing, just for the sake of it and then they also worship Nocturnal, the evil goddess of the night. … Nothing you can do. You can’t report them. You can’t tell them to never steal again. You can’t kill them (most of them are immortal).

In Beyond: Two Souls:

There is a scene where you are supposed to assassinate a “warlord”. On your way to him you get some hints that he might not be a warlord, and there is no way to not kill him, even if you have a strong suspicion that he is innocent or if you have played it before and know that he is innocent.

In inFamous:

Your girlfriend is kidnapped, and you have the choice of saving her, or saving some doctors. If you save the doctors, she dies. If you try to save her, it’s a ruse and she was with the doctors. No matter what you do, she dies.

One downside of moral systems is that support for a choice-by-choice or non-binary morality is often less robust. Many gamers, in free-response, expressed some annoyance with systems that would lock out powers or dialog to someone who played games on a choice-by-choice basis instead of choosing a clear good or evil path: “Mass effect is beyond guilty of this. You’re either good or you’re evil, there is no middle ground, you don’t have freewill.” “By taking the middle ground, you lose the opportunity to make the decisions that give the best outcome,” said another commenter, referring to this same game’s tendency to lock out dialog options based on morality. A similar system appears in the game inFamous, where one commenter wrote: “When you went either fully for the evil or fully for the good path, you’d get very strong powers. When going with the middle road, you wouldn’t really get anything special.”

What Counts as Rewarding?

Story-focused gamers seem to be guided by their internal moral compass rather than alternative systems of morality. They are willing to experiment with alternatives only on their second playthroughs.

Can we do better at encouraging gamers to engage decisions differently? What might tempt a player to make a non-traditional moral choice?

82 percent of participants said “game story” was their primary motivation in a moral choice game. Story trumped mechanical advantages or game rewards, such as Achievements. In some games, such as Fable, moral choices have an effect on the appearance of the player’s avatar, but this was the primary motivator to only 5 percent of participants.

Gamers may prefer the intrinsic reward of feeling good about their behavior over in-game material rewards. While theft and murder does tend to get players more money, it does not seem to be a strong enough temptation to lead players into full-time evil play. “Evil in Fable tends to make a LOT more cash,” said one gamer. Another said: “The ‘good’ path doesn’t allow for a lot of deviation, and often requires a player to be financially poor, as if the morally upright path is unfailingly narrow, uncreative and destitute.”

It’s important to acknowledge that even single-player games have a social aspect. Pressure in clan and fan spaces may exist for players to “behave” rather than take actions that might do harm to well-liked fan characters. This study did ask about those kinds of social pressure, but a more in-depth study of specific games may discuss the influence of games’ fan culture on moral choices.

Conclusions

It’s possible that games with binary morality are going out of style. The Walking Dead (Telltale Games, 2012) is a game that’s often cited as a game with more nuanced moral choices. Fallout: New Vegas (Obsidian Entertainment, 2010) and Dragon Age were also well-liked by respondents because choices were faction-based or character-based rather than always simply good or evil. Several gamers reported they enjoyed the binary choice systems in Mass Effect and Fable (“I liked the style of Fable … You could make your choices either way, and there were rewards and consequences for each choice”), but others were negative about these same systems (“Fable, the choices are always too extreme”). Gamers seemed to feel happiest when their choices affected the story and upset if they perceived their choices did not.

Many questions remain unanswered. Is it worth it to developers to create evil content in games, knowing how few gamers will deliberately seek it out? Is it worthwhile to create games assuming they’ll be played twice, and, if so, how different should the branches be? Is there a good way to tempt gamers to put themselves in another person’s shoes, or do they generally just want to “do the right thing”? Gamers like myself might regret it if the ability to play an evil character was removed from some games. Can we develop games where being the bad guy is really the most fun? Should we?

Some gamers will not do evil, even when it seems like they’re up against the wall:

- In Heavy Rain, protagonist Ethan Mars is forced by a serial killer to go through a series of trials to receive letters to an address where Ethan’s son is being held. One of the later challenges involved having to kill a man to get more of these letters. In my first playthrough, I spared the target’s life and later in the game Ethan had to determine the location of his son with the letters he had (if I had killed the one man in the first place, Ethan would have earned all the letters to the location).

- In Heavy Rain, I put away the gun instead of shooting an unarmed father during the Bear Trial.

- Heavy Rain, where it deliberately tried to make me kill a person I didn’t know …

- … in Heavy Rain, I had the choice of killing a guy in his daughter’s bedroom but I spared him because he was a father.

(Survey responses regarding Heavy Rain)

When I, as Ethan, stood standing next to the man, his head down, pleading, I considered the options. I watched him beg and listened to his cries. But: dammit, I’m in it to win it, I said to myself… and I pulled that trigger.

There is one way designers can get gamers to sin reliably. Just hide the heroic option.

Spec Ops: The Line. … The game puts me back in control, in a third-person shooter, with an automatic rifle. The crowd has surrounded me, and is shouting, angrily. They’re throwing rocks. There’s nowhere to run, and nowhere to hide, and I’m actually taking damage. If I do nothing, I’ll die. But I refuse to fire. I’m immediately reminded of the Boston Massacre, and of the countless other times this scene must’ve played out, and I refuse to fire my assault rifle on people armed with rocks. Still, I had to do _something_. They were throwing rocks. In the end, I used a melee attack, which is _probably_ nonlethal. The game interpreted this as a different choice — my partner shot into the air (which I could have also done), and the two of us chased off the natives. Zero casualties, that time. And an achievement: “A Line, Held.” Here is a depressing fact: http://steamcommunity.com/stats/SpecOpsTheLine/achievements 22% of players have “A Line, Held.” 31.6% of players have “A Line, Crossed. (Anonymous survey response)

Video games can allow players to live out their fantasies of being heroes or villains. This study found that villainous fantasies seem to be much less common than developers think, or than they account for. A better way forward may be to create choices that allow players to see the world from someone else’s point of view. Games that force players to pause and consider the ramifications of their actions may lead to more meaningful experiences for players.

Most players want to make “the right choice” when it’s easy, marked, and clearly labeled. But a future of more nuanced choices may point to a stronger direction for the medium. If gamers are not interested in being evil, we can get more traction by instead questioning what they believe to be good. That way, there’s more to game morality than choosing what color of cupcake they receive.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge Heidi McDonald, Sheri Graner Ray, and Ryan Lange for their help in the development of this instrument and study. Thank you!

Bio

Amanda Lange is a game critic and designer currently living in Pennsylvania. She has contributed to serious games, indie games, and social games and has taught game design and writing classes. She has also spoken internationally about online community management. She is a staff contributor at www.tap-repeatedly.com and does her own personal writing at second-truth.blogspot.com.

References

Bethesda Game Studios. (2008). Fallout 3. Multi-platform: Bethesda Softworks.

Bethesda Game Studios. (2011). The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim. Multi-platform: Bethesda Softworks.

Big Blue Box. (2004). Fable. Microsoft Games Studio & Feral Interactive.

BioWare. (2012). Mass Effect 3. Multi-platform: Electronic Arts.

Citizen, J. (2012). BioWare donates 400+ protest cupcakes to charity. Player Attack. Retrieved from http://www.playerattack.com/news/2012/03/29/bioware-donates-400-protest-cupcakes-to-charity/

Fogel, S. (2012). Telltale Games: The majority of The Walking Dead players try to do the right thing. Venturebeat. Retrieved from http://venturebeat.com/2012/08/15/telltale-games-the-walking-dead-statistics-trailer/

Irrational Games, 2K Australia, Digital Extremes, Feral Interactive, & Demiurge Studios. (2007-2009). BioShock. Multi-platform: 2K Games & Feral Interactive.

McDonald, H. (2013). Narrative as a tool for inclusiveness. Presentation at the annual meeting of the Gotland Games Conference, Visby, Sweden. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ofGKxxUa2K0

Molyneux, P. (2013). PAX Prime 2013 story time with Peter Molyneux. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F4LdFDL35Oo

Obsidian Entertainment. (2010). Fallout: New Vegas. Multi-platform: Bethesda Softworks & Namco Bandai Games.

Phillips, T. 2012. Fewer players finished Mass Effect 3 than completed Mass Effect 2. Eurogamer. Retrieved from http://www.eurogamer.net/articles/2012-08-13-less-players-completed-mass-effect-3-than-finished-mass-effect-2

Rockstar North, et al. (2013). Grand Theft Auto V. PlayStation 3 & Xbox 360: Rockstar Games.

Rockstar San Diego & Rockstar North. (2010). Red Dead Redemption. PlayStation 3 & Xbox 360: Rockstar Games.

Schreiber, I., et al. (2009). Group report: Choosing between right and right: Creating meaningful ethical dilemmas in games. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Game Design Think Tank Project Horseshoe. Retrieved from http://www.projecthorseshoe.com/ph09/ph09r3.htm

Snow, B. 2011. Why most people don’t finish video games. CNN Tech. Retrieved from http://www.cnn.com/2011/TECH/gaming.gadgets/08/17/finishing.videogames.snow/

Totlio, S. 2013. Two thirds of you played Mass Effect 3 as a paragon. Mostly as soldiers. Kotaku. Retrieved from http://kotaku.com/5992092/two-thirds-of-you-played-mass-effect-3-as-a-paragon-mostly-as-soldiers

Yager Development. (2012). Spec Ops: The Line. Multi-platform: 2K Games.